There is an age-old paradox inherent in any attempt to “live a better life”, or “to better oneself” consciously: your life reflects who you are, and you are shaped by your life. To change your life, you’ve to got to change yourself; and to change your self, you’ve got to change your life; so where to begin? Whether you want to or not, you find yourself in the position of Baron Munchausen trying to pull himself (and his horse) out of a swamp by his pigtail (I believe this is called “bootstrapping” nowadays).

I was reminded of this paradox when I read the following passage from Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s book on “Creativity”, where he explains why it makes sense — for any one of us — to study lives of extraordinarily creative people:

“Their lives suggest possibilities for being that are in many ways richer and more exciting than most of us experience. By reading about them, it is possible to envision ways of breaking out from the routine, from the constraints of genetic and social conditioning, to a fuller existence. <…> Indeed, it could be said that the most obvious achievement of these people is that they created their own lives. And how they achieved this is something worth knowing, because it can be applied to all our lives, whether or not we are going to make a creative contribution.”

Is it really possible to change one’s life in this way, just by learning how extraordinary people live theirs?

I believe it is, if only because sometimes it’s just a matter of removing a “blind spot”: you suddenly see a possibility for change in your environment — maybe something easy, small, seemingly insignificant — which will turn out to be a catalyst for further changes, in your life and in your self, the beginning of a new path.

What resonated with me most in Csikszentmihalyi’s book is what he says about the role of our visual environment: beauty not just a source of pleasure and fleeting enjoyment, but as a shaper of our thoughts and feelings. I did read before about stubborn scientific problems magically solved when a scientist all but gives up and goes on vacation to one beautiful place or another — but I used to assume all these stories were mainly about letting one’s thoughts incubate below the threshold of consciousness rather than about the role of beauty in this process.

I now think it might have been a wrong assumption. Csikszentmihalyi writes:

“The belief that the physical environment deeply affects our thoughts and feelings is held in many cultures. The Chinese sages chose to write their poetry on dainty island pavilions or craggy gazebos. The Hindu Brahmins retreated to the forest to discover the reality hidden behind illusory appearances. Christian monks were so good at selecting the most beautiful natural spots that in many European countries it is a foregone conclusion that a hill or plain particularly worth seeing must have a convent or monastery built upon it.”

A possible reason for this, he suggests, is that complex and harmonious sensory experiences influence our cognition even when we don’t focus on them, and lead our minds to “novel and attractive patterns” — not a simple causal connection (just go to a beautiful place, and your mind will overflow with beautiful solutions and beautiful thoughts), but a connection nonetheless.

What, then, about art? — not as a grand transformative experience one might have in a museum, or in the Sistine chapel, but as something just silently present in the visual environment of your life, often below the threshold of conscious attention.

There is a chapter in Csikszentmihalyi’s book about what people make of their home (and office) environments — and this, of course, applies not only to extraordinary people, but to every one of us. He writes:

“In one of my studies we interviewed two women, both in their eighties, who lived on different floors of the same high-rise apartment house. When asked what objects were special to her in her apartment, the first woman looked vaguely around her living room, which could have passed for a showroom in a reasonably pricey furniture store, and said that she couldn’t think of anything. She gave the same response in the other rooms—nothing special, nothing personal, nothing meaningful anywhere. The second woman’s living room was full of pictures of friends and family, porcelain and silver inherited from aunts and uncles, books she loved or that she intended to read. The hallway was hung with framed drawings of her children and grandchildren. In the bathroom the shaving tools of her deceased husband were arranged like a tiny shrine. And the life of the two women mirrored their homes: the first followed an affectless routine, the second a varied, exciting schedule.”

Here, of course, there is no simple and direct causal connection either: its not like the homes of the two women created their lives all by themselves. It seems much more likely that each woman created her own home and her own life: the same difference between them that we see in their homes is also reflected in their lives. After all, we are who we are, and changing our home decoration won’t change that, right? We are back with Baron Munchausen, and his horse, and his pigtail…

But let me tell you a story about myself, and how home decoration saved my life…

In 1996, we moved to Germany because I accepted a job at the University of Bielefeld. This town, Bielefeld, had been almost completely ruined by the Allied aviation during the Second World War, and then rebuilt in the spirit of austerity and pragmatism: reasonably comfortable, but without a touch of beauty. We rented a furnished apartment; it used to belong to the owner’s elderly mother, and the furnishings reflected that — it probably looked similar to that old woman’s apartment visited by Csikszentmihalyi. I remember there were remote controls for the bed and for all armchairs and only one small writing desk (certainly not enough for our family of three).

I was completely focused on finding my way in the university, learning to teach in a rather unfamiliar language, arranging my son’s school matters, dealing with the quirks of department head’s temperament, and so on, and so forth — the usual routine of life, made more stressful by the move to another country. Our visual environment wasn’t on my list of priorities. In retrospect, I believe I took it as an immutable fact of this new life, without giving it a moment’s thought.

But then we went to Paris for a few days, and somewhere, in a small street behind Musée d’Orsay, serendipitously found a small dark shop filled with heaps upon heaps of reproductions in various sizes. Believe it or not, the idea that we can add reproductions of our favourite paintings to our environment in Bielefeld had not even crossed my mind before this chance encounter — it was only then that I understood clearly what had been missing in my life all along.

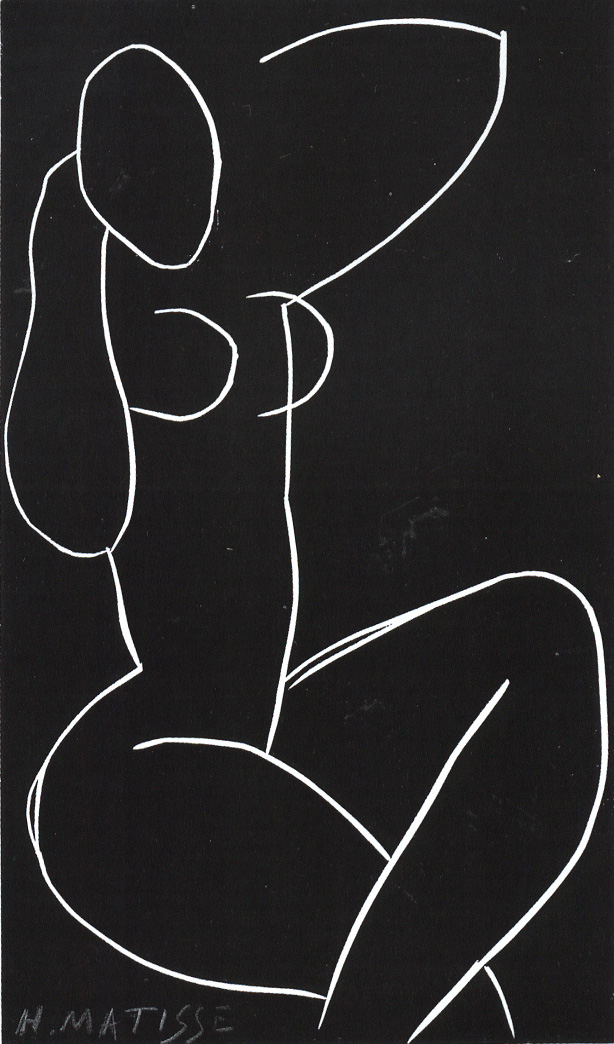

I don’t remember how much time we spent there, browsing through all these heaps of prints, but we went away with several huge posters to bring back — Chagall, Matisse, Van Gogh — most of them for our apartment, and a nude by Matisse for my office (the very anticipation of shocking my head of department was just too tempting to resist; to his credit, he took it in his stride, which had the unexpected effect of improving our working relationship).

It would be a lie if I told you that our life changed miraculously once these posters were hanging on the walls of our Bielefeld apartment— all problems resolved, stumbling blocks dissolved, research ideas flowing freely and happily. Not quite. But it had certainly become much more of a life: I was feeling more alive every day, there seemed to be more reasons to get up in the morning, more laughter, more research, more trips to beautiful places.

What is probably more important and more to the point, I began to see more aspects of my life as changeable: seemingly unbreakable constraints and routines were being gradually unmasked as limiting but transient illusions. To repeat Csikszentmihalyi’s words, I was growing more and more aware of “ways of breaking out from the routine, from the constraints of genetic and social conditioning, to a fuller existence”. Now — nearly twenty years since that trip to Paris — I see that my life and my self have transformed completely, or at least more than I could have imagined then; this seemingly small change opened a path to revitalising — and living — my childhood dreams.

Does it all sound like one of Baron Munchausen’s adventures?

Have I pulled myself out of a swamp by my own pigtail (which doesn’t even exist)? I don’t think so — I believe it was the presence of Matisse, Chagall and Van Gogh that pulled me out. Since then, I had never again forgotten that I need paintings on my walls to be alive, and our collection of printed reproductions had been constantly growing before (much, much later) I began to replace them with my own oil studies of my favourite paintings.

And yet I obviously used to have this “blind spot” before that visit to Paris: I didn’t see what was lacking, even though the depressing emptiness was right in front of me. That’s what I recalled when I read about this old woman living in a showroom of a furniture store — maybe it’s not really who she was at all. Maybe she could have lived a different life — but no serendipitous occasion had helped her to recognise a similar “blind spot”, to become aware of what’s missing, what can be changed in her environment.

I wish I had a time machine to go back and give her the right poster for her wall — for some reason, I imagine a nude by Matisse might have amused her… After all, if it did amuse my department head in Bielefeld, then everything seems possible.