Abstract concepts don’t invoke emotions…

— I heard this in a business course the other day.

But is it true?

What about eternity?

An abstract concept, living in the mind, with no grounding in sensory reality — except this longing in the human heart, which no abstract concept can invoke…

Alan Lightman writes:

To my mind, it is one of the profound contradictions of human existence that we long for immortality, indeed fervently believe that something must be unchanging and permanent, when all of the evidence in nature argues against us. I certainly have such a longing. Either I am delusional, or nature is incomplete. […] Despite all the richness of the physical world — the majestic architecture of atoms, the rhythm of the tides, the luminescence of the galaxies—nature is missing something even more exquisite and grand: some immortal substance, which lies hidden from view.”

Alan Lightman, “The accidental universe: the world you thought you knew”

Hidden from view… but is it?

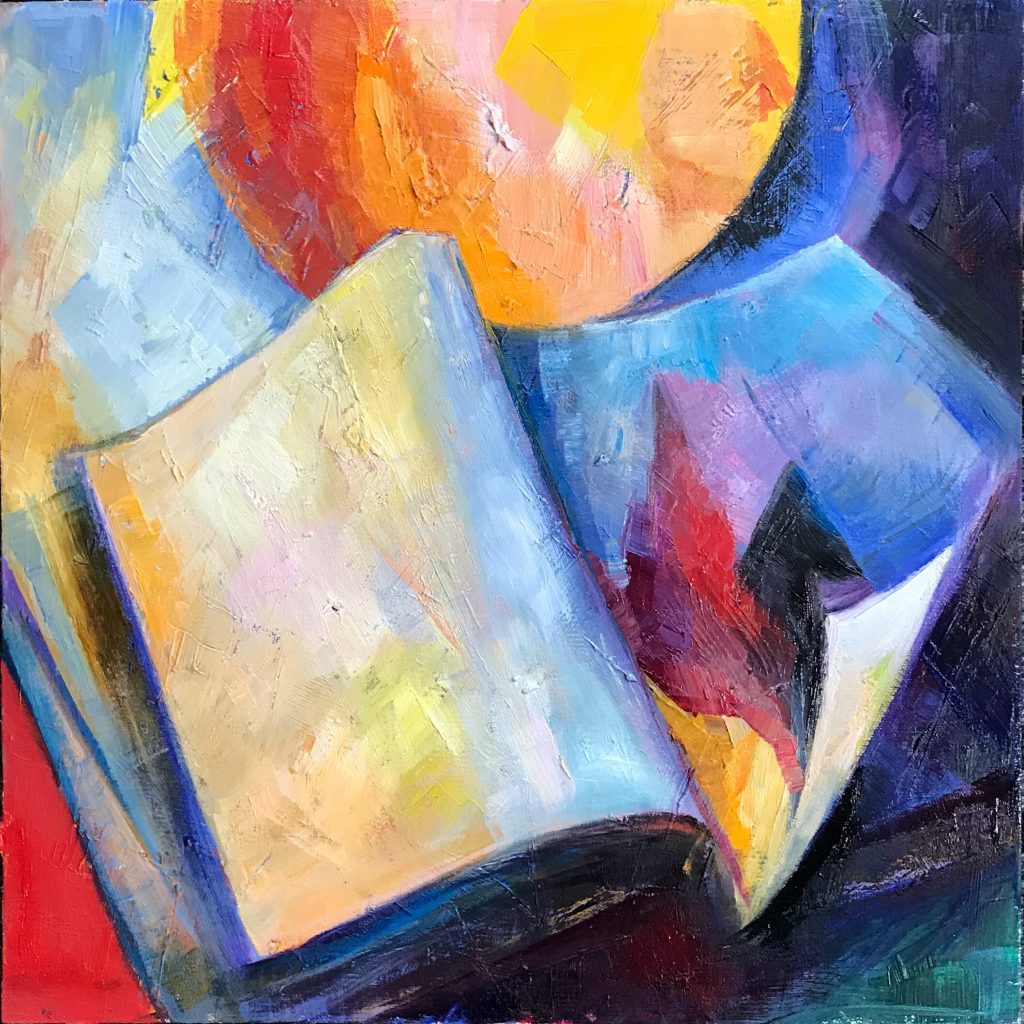

I painted this lemon on two consecutive days this week, at different times of day. Can you see that the two lemons in the painting belong to different moments in time? Here is a better photo:

What happened to these moments when they re-emerged in the painting?

Is there Time in painting?

Art is a shortcut to Eternity

— this was my mind’s staircase response to the first conversation in our “Art and Consciousness Circle”.

It seems so obvious in retrospect… Haven’t I always known this — that this is what it is all about? But somehow, I made myself forget — and keep forgetting.

In January, we talked about Kandinsky’s “three mystical elements” of artist’s inner necessity — this ever-present inner impulse that calls us to work.

The three elements, according to Kandinsky, are:

- the artist’s personality (self-expression)

- the spirit of the age (the element of “style”), and

- “the element of pure artistry, which is constant in all ages and among all nationalities”, “an expression of the eternal artistry”

Kandinsky calls the first two elements “subjective”, and the last one, “objective” (words which seem to become more confusing with every usage)…

There is an implied hierarchy here, which made us all uneasy — especially because Kandinsky writes:

“A full understanding of the first two elements is necessary for a realization of the third…”

Wassily Kandinsky, “Concerning the spiritual in Art”.

Does he mean that our only path to the eternal lies through the transient, through the forms and styles of our age and our culture?

I don’t think so, because a bit later, he writes:

The inevitable desire for outward expression of the objective element is the impulse here defined as the “inner need.”

… thus placing the eternal firmly within an individual human being. Eternity’s hostage imprisoned by Time, in Boris Pasternak’s timeless words.

“Beyond all date, even to eternity… “

— this is from Shakespeare’s sonnet 122, the sonnet I started translating into colour this month. And he continues:

Or, at the least, so long as brain and heart

Have faculty by nature to subsist …”

There was a time, in the unfolding of the sonnets sequence, when this tension — between the idea of eternity and the mortality of human vessels of this idea — was unbearably painful to him.

But now, the verse glides from one to another as though there were no space in between — easily, effortlessly. Or simpler still:

as though the poet were the space that holds them both (as he does)… and that is enough.

A shortcut to eternity — this is what my strange and weirdly personal relationship with Shakespeare really is…

When you feel a deep inner resonance with a work of art from another age, beyond the trappings of style and personality, it is Kandinsky’s “third mystical element”, the “objective”, the eternal, revealing itself to you across time and space.

Far from being “hidden from view”, it does all it can to make itself seen and felt… the rest is up to us.

Kandinsky writes about this, too:

An Egyptian carving speaks to us today more subtly than it did to its chronological contemporaries; for they judged it with the hampering knowledge of period and personality. But we can judge purely as an expression of the eternal artistry.”

A child of my knowledge-hungry age, I cannot always resist the temptation to enfold Shakespeare in whatever hampering historical knowledge I can find (did you know, by the way, that in Shakespeare’s English, art and heart were indistinguishable in pronunciation?)

But perhaps Kandinsky is right: this is not how this connection really happens.