There is no God but God, and his name is William Shakespeare. Yahweh is not God. William Shakespeare is God. Heinrich Heine said, “There is a God, and his name is Aristophanes.” On Heine’s model, I again remark: there is a God, there is no God but God, and his name is William Shakespeare.

— Harold Bloom.

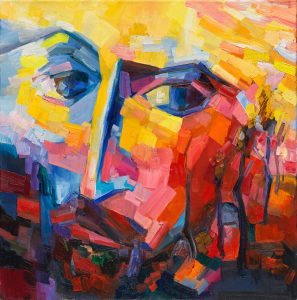

The idea of painting the sonnets first surfaced in my mind in 2011, as I was reading Helen Vendler’s book, The Art of Shakespeare’s Sonnets. There was something about her way of thinking about the art of sonnets that resonated with my way of thinking about the art of painting, powerfully and unmistakably.

The idea felt audacious, for sure, but just crazy enough to try. It took me several months to think it through and finally start painting (I used to be a queen of overthinking. One of many, many things Shakespeare has cured me of in these seven-plus years of painting — and living — his sonnets. Well, almost cured. But the series isn’t over, so I am hoping for the best.)

These seven years, this journey Shakespeare took me on, turned out to be the most extraordinary and transformative part of my life (with the only exception, perhaps, of its very first seven years). There were things to discover, and things to let go of — in particular, the idea of being right.

T.S.Eliot said:

About anyone so great as Shakespeare, it is probable that we can never be right; and if we can never be right, it is better that we should from time to time change our way of being wrong.

Painting the sonnets is a deliciously dramatic way of being wrong about them.

It is not even exactly being wrong about the sonnets, but rather with them, or even within them.

They call me to stay within their puzzling space for as long as it takes, to surrender the neural fabric of my being to their eternal interplay of rhythms and paradoxical, ambiguous meanings, to become an empty vehicle for the emergence of this interplay into the realm of visual experience.

For its painting translation to emerge, the sonnet has to sink so deep into my being, so that the very pulse of my life synchronises with its iambic beat, and my perspective shifts:

I am no longer a reader separated from the sonnet by four centuries of human history. My “I” merges both with the “I” and the “thou” of the sonnets, taking them completely out of their historical time and space and bringing them into the here and now.

Just read these lines from the very first sonnet:

But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed’st thy light’s flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel.

In the traditional, historical way of being wrong about the sonnets, these lines are addressed to a young man who, more than four hundred years ago, didn’t want to marry. A young man whose identity is still controversial, but whose child-free stance is as utterly irrelevant to us as it gets.

But what if we listen to these lines as though they were addressed directly to us, to the humankind of the twenty first, about to destroy the planet that sustains it? The humankind that literally, not metaphorically, is making a famine where abundance lies? By the way, this is how the sonnet ends:

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee.

In my painting process, this shift of perspective happens not mentally, and not even emotionally — but rather neurally — at the deep level of this mind-body system to which only painting gives me access (I didn’t really know why this sonnet translated as a burning landscape; it just did).

In the seven years I have spent in the space of the sonnets, the sequence has been emerging as this living presence — as an urgent message to humanity, which, for some reason, just wanted to be translated into the language of colour at this time.

Richard Rudd writes:

The poet T.S. Elliot said that as far as literature is concerned, “The world is divided between Shakespeare and Dante — there is no third.” <…> in his supreme work The Divine Comedy, Dante left us what is arguably the greatest map of human consciousness ever written. Whereas Shakespeare used drama, Dante used allegory as a means to communicate an immortal truth about human nature. The Divine Comedy essentially describes the geography of consciousness as it moves from the lower frequencies to the very highest.

In Shakespeare’s sonnets, this breathtaking range of consciousness is found not in Dante’s grand metaphysical realms, but in the mess and glory of human love stories, in our longing and our joy, in our sacrifices and our betrayals — in the realm of earthly human experience. Our inner hell and our inner heaven, playing with one another within the space of a single sonnet (or even a single line).

The idea of painting the sonnets definitely doesn’t feel like it originated in me. If not for this sudden flash of inspiration, I (the me of eight years ago) would have never even dared to contemplate it. It feels as though the sonnets just wish to be translated into colour at this time.

Why?

To be frank, I don’t really know, but if I were to guess, it is because paintings give them different kind of presence — more visible, more outwardly material, capable of being with us, and enlivening our living spaces, even when our minds are elsewhere. These translations allow the sonnets to enter the realm of sensory experience, to transform our visual environment.

To look at a selection of sonnet paintings, please click here.

If you would like to learn more about Shakespeare’s sonnets, the story of painting them and what it has taught me about love and life, please click here.