I woke up just before sunrise on the morning of January 1, in a hotel room overlooking Half Moon Bay Harbour, and went to the balcony.

The first raspberry-coloured streaks of light of 2018.

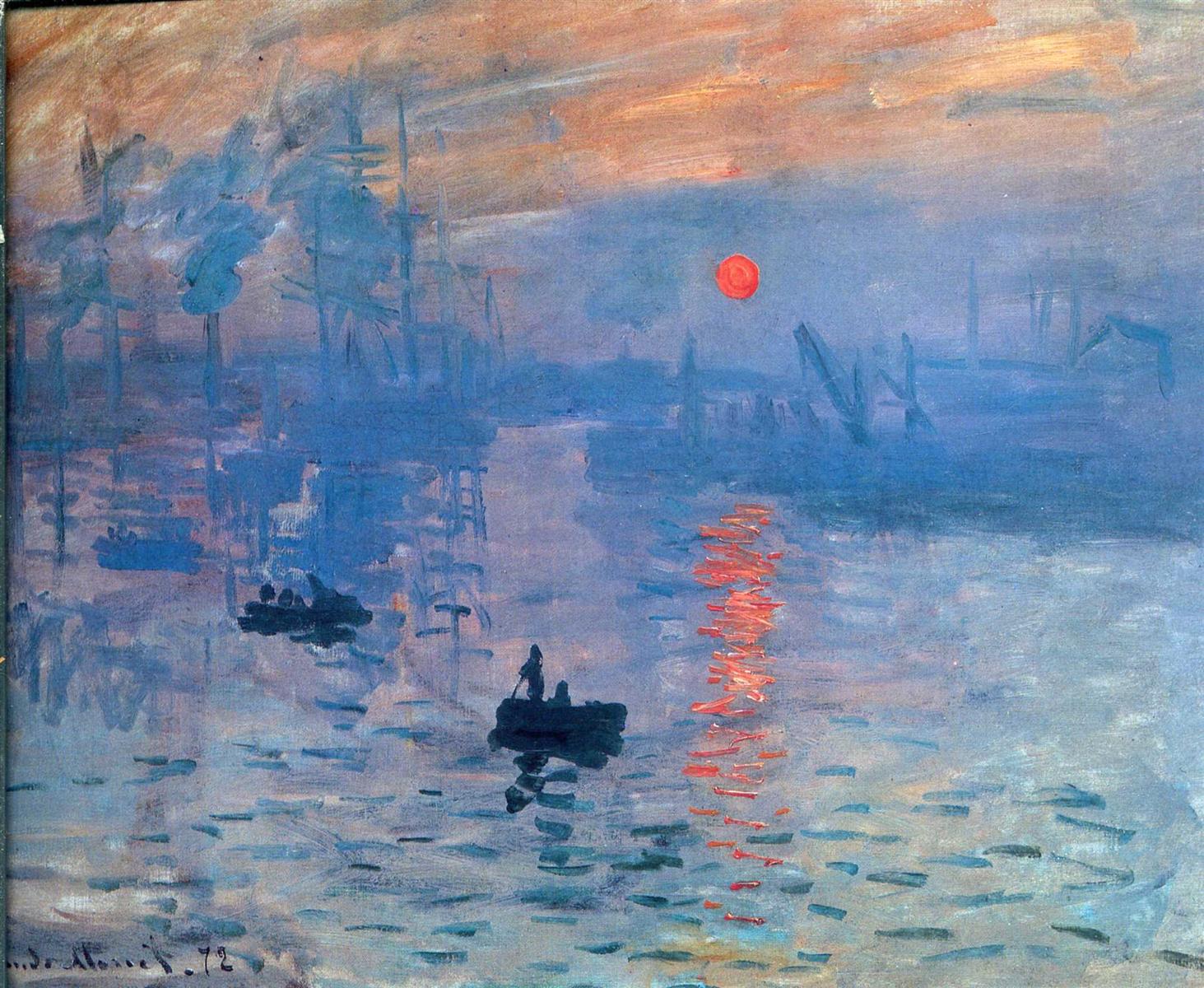

A perfect Claude Monet moment, I thought. Unrepeatable, irreplaceable, fleeting.

And so I pulled out a panel from the day before (a failed attempt to capture the last sunset of 2017), put my “painting” windbreaker over my pajamas, and did my best to do the impossible.

Not only was the light changing every second, but even the boats were slowly turning around, in surrender to the mild waves of the harbour.

When I started, the mass of mountains and the harbour were fused into one huge and strange dark shape, and the boats were but black spots in the ocean of flickering light. But everything was growing lighter and clearer under my brush, the blues warmer and warmer, the yellows and the pinks, more and more intense.

Sooner or later, any plein air painter learns not to “chase the light”. The idea is to choose a moment one wants to capture, and stick with it to the best of one’s abilities, disregarding the changes in front of your eyes.

But this morning, this practical skill seemed utterly futile. Not only that, it would have made the whole experience meaningless.

All I could do was just stay there with the change, true to each next moment, however different it was from the previous one, watching the sun rise and work its alchemy.

The grand illusion of painting: a pause in the flow of time.

The spacetime of painting is always larger than a moment of time, and all impressions within this spacetime somehow merge into something that LOOKS like a single moment. But it is something different, a delicate marriage of a moment and a flow.

Something that can only exist in the space of a painting.