[line]

The other two, slight air and purging fire,

Are both with thee, wherever I abide;

The first my thought, the other my desire,

These present-absent with swift motion slide.

For when these quicker elements are gone

In tender embassy of love to thee,

My life, being made of four, with two alone

Sinks down to death, oppressed with melancholy;

Until life’s composition be recured

By those swift messengers returned from thee,

Who even but now come back again, assured

Of thy fair health, recounting it to me:

This told, I joy; but then no longer glad,

I send them back again and straight grow sad.

William Shakespeare. Sonnet 45

[line]

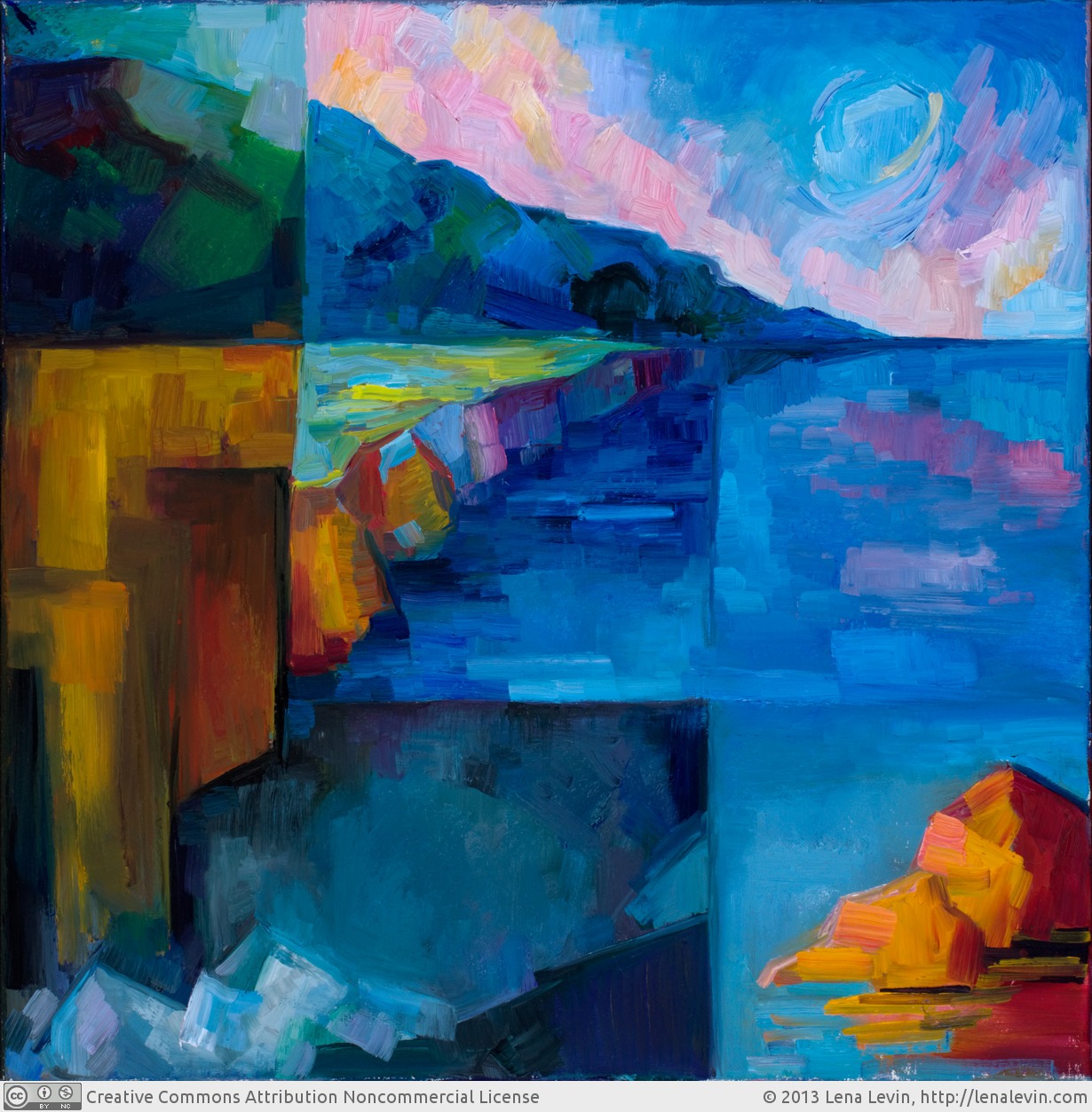

This is the second painting of the diptych for two sonnets, forty fourth and forty fifth; in a sense, another essay on the same question: the source of landscapes’ power to touch our emotions, to express a state of mind.

The first painting explores one answer, suggested by the theory of four elements: looking at a landscape is like looking into the inner life of a human being because they are composed of the same fundamental elements. Another answer — or maybe just another version of the same answer, I am not sure — has to do with the way our brains create what we see from the input of our senses.

What one sees, and how one sees it, is not just “what is there”. The image is modulated by the beholder’s state of mind. The brain doesn’t just perceive what’s presented to the eyes; it creates an image based both on the sensory information and on its own state — it’s not for nothing that “rose-coloured glasses” became an idiom. And a painted landscape — in contrast to a natural one — contains as it were both the view and a pair of mind-altering glasses created by the painter: as the beholders share in the way the artist re-created the view, so they share in the state of mind intrinsic to this recreation.

It doesn’t mean, of course, that the state of mind perceived by the beholder is identical to the state of mind consciously intended (or unconsciously channelled) by the artist; nor that you and I will have the same emotional reaction while looking at the same painting. Obviously, each viewer adds their own “inner glasses”, tinted by their own mood and life experiences, and their brain recreates the image once again (by the way, looking at a painting together with friends opens this quite unique channel of communication — an opportunity to compare your ways of seeing the world).

Even if the viewers’ perceptions will inevitably vary, and the artist knows that, a landscape usually represents a unified, harmonious image: in a sense, one state of mind, one mood. But this conventional approach wouldn’t do for painting the forty fifth sonnet, where the mood changes back and forth quickly, as though something happens within the time frame of writing the sonnet, even but now:

Until life’s composition be recured

By those swift messengers returned from thee,

Who even but now come back again, assured

Of thy fair health, recounting it to me:

This told, I joy; but then no longer glad,

I send them back again and straight grow sad.

Some commentators believe that these assurances of fair health must come from a letter (arriving just as the poet is pouring his depression into the sonnet).

I don’t think so. The whole point of the sonnet is in this incredible swiftness with which one’s thoughts and desires move (sliding from here to there and back):

The first my thought, the other my desire,

These present-absent with swift motion slide.

I believe it has nothing to do with letters, and everything to do with the very nature of our thought processes, and the barely controllable rapidity of their unpredictable jumps from place to place, from subject to subject, from memory to imagination. Our thoughts don’t need letters (or any other external stimuli) to change from moment to moment; they change all the time as it is (unless one happens to be fully immersed in something truly challenging and/or exciting — but more about this later).

In my experience, there are people who know this about themselves, and those who don’t. Maybe there are even some sages who are exempt (from what I’ve read, a lifetime of meditation practice can probably do that to a person), and it’s never a good idea to generalise too broadly from one’s own experience — people, I am finding, may differ from one another more than we (or I, at least) tend to assume. Still, I believe that some people are unaware of this swift motion within themselves simply because consciousness does its best to conceal it from us and present itself as a more consistent and reliable guide to reality than it is. As Tor Norretranders writes in his book on consciousness, it is a very good liar. But these lies can be unmasked with a smallest attempt at introspection: just close your eyes, wait for the first thought to occur and make your best effort to keep it there, in the focus of your conscious attention, unchanged.

My guess is that you’ll find your thoughts flying somewhere else fairly quickly, within a minute; suddenly, you are somehow — you don’t know why and wherefore — thinking about something else entirely. If that’s the case, you are in good company, because this, I am sure, is what this sonnet is about.

So am I trying to say that a human being is incapable of consistently focused thinking (not even Shakespeare)?

Of course not. The modern science seems to have discovered the neural underpinnings of two “modes”: one is a mind concentrated, immersed in something, “in the flow”, and the other is a mind left to its own devices, wandering, “absent” (they call the latter “default mode”). It’s in the “default” state that one’s thoughts and desires jump from “here and now” to other places (and moments in time) all the time.

My guess is that focusing on the very experience of one’s thoughts and desires being elsewhere — concentrating enough for the experience to emerge as a poem — would “switch” the brain’s mode to the state of complete immersion in the process. If so, then it is this immersion in creating a sonnet that brings the thoughts and desires (slight air and purging fire) back to the poet to restore life’s composition — even but now — and then this meta-experience itself goes into the poem, too. But once it’s recognised for what it is, the thoughts and desires immediately go straight back to the original experience of separation and longing.

Where does this leave me as far as my painting “translation” is concerned?

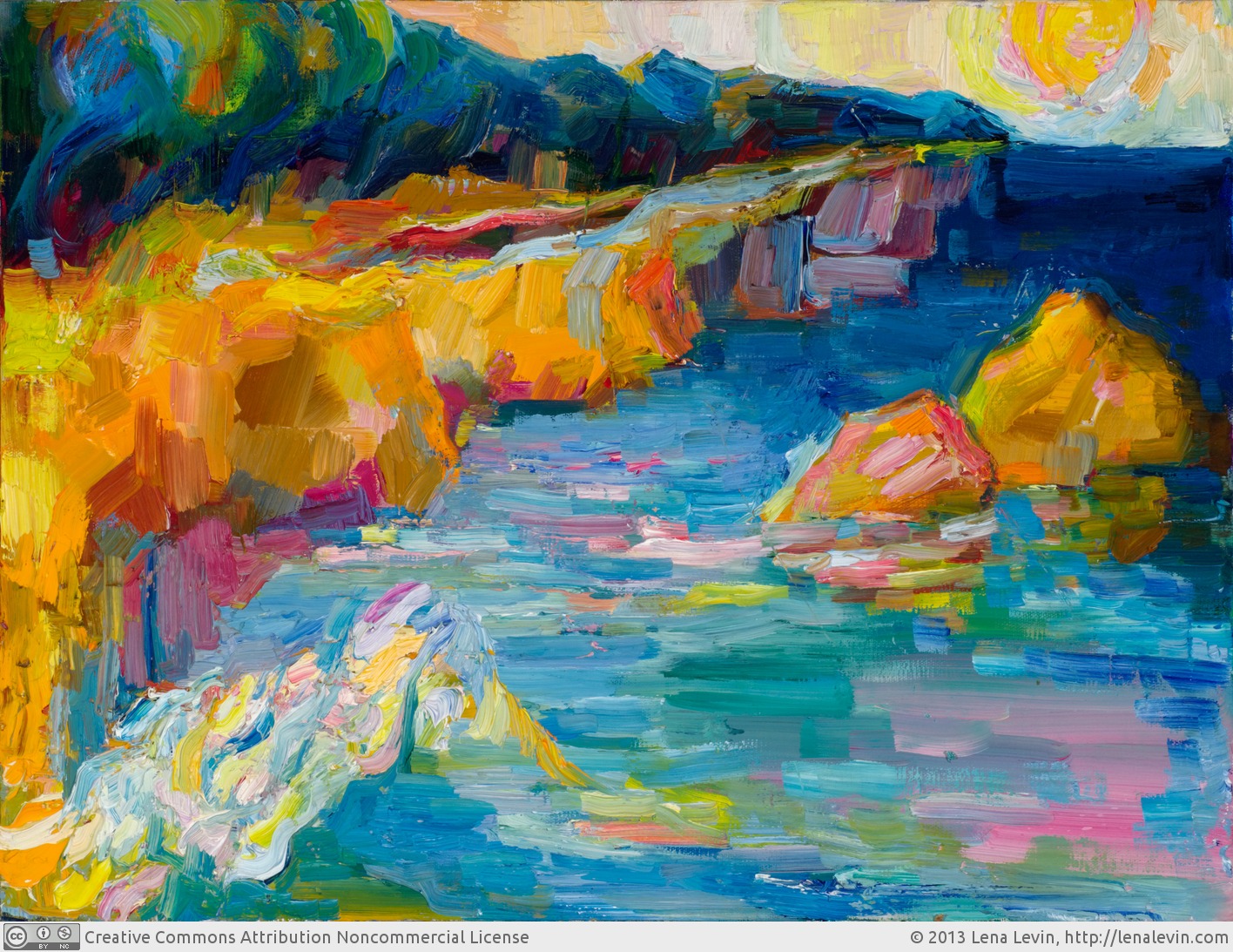

The thing is, the painting process — at its best, at least — has the same effect; it vacillates between a state of mind (or an emotional state, if you wish) the painter brings to the view to begin with and the (completely different) state of focused interaction between the painter and the painting, the flow of painting — when life’s composition is restored. At a risk of oversimplification, there is a joy in a painting going well even if it expresses (or is intended to express) sadness. My challenge, then, was to express this meta-experience of swift vacillation in a single painting (while still holding the painting together as a unified visual impression).

To do so, I have made a compositionally risky decision to follow the sonnet in its reliance on the theory of four elements and four humours.

The view itself contains, of course, all four elements — earth, water, air and fire (if you accept the sun as a manifestation of fire). It is, originally, a real-life view from Anchor Bay in Northern California; the painting is based on this plein air study.

But the four elements also make their appearance as “states” of human mind, in the way — or, to be more precise, in the multiple ways — the view is re-created in the painting. The painting is structured as four overlapping squares — roughly corresponding to water, earth, fire and air if you look at the painting clock-wise beginning from the bottom left. I think of them as four semi-transparent slides, four pairs of “inner glasses” through which the inner state of mind modulates one’s way of seeing what’s presented to the senses.

In the centre of the painting, where all four squares overlap, all elements are united to recure life’s composition.

[share title=”If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, please consider sharing it with your friends!” facebook=”true” twitter=”true” google_plus=”true” linkedin=”true” pinterest=”true” reddit=”true” email=”true”]