Even when I first started thinking about painting Shakespeare’s sonnets, I knew that Time would be the crux of this project. Not just because it’s one of Shakespeare’s central themes, and not even just because the sensation of Time is such an essential aspect of human experience. I was fascinated and overwhelmed by the radical differences in how poems and paintings can represent Time, express Time, and even situate themselves in Time.

A poet has all the means for expressing Time accumulated by their language — words, metaphors, tenses. Add to this rhythms and meters, which enact and measure Time within the space of the poem. A poem can jump from the present to the future to the past easily and naturally, like thought, and imposes its own time flow on the listener (or reader), its own stresses and pauses, word after word, line after line.

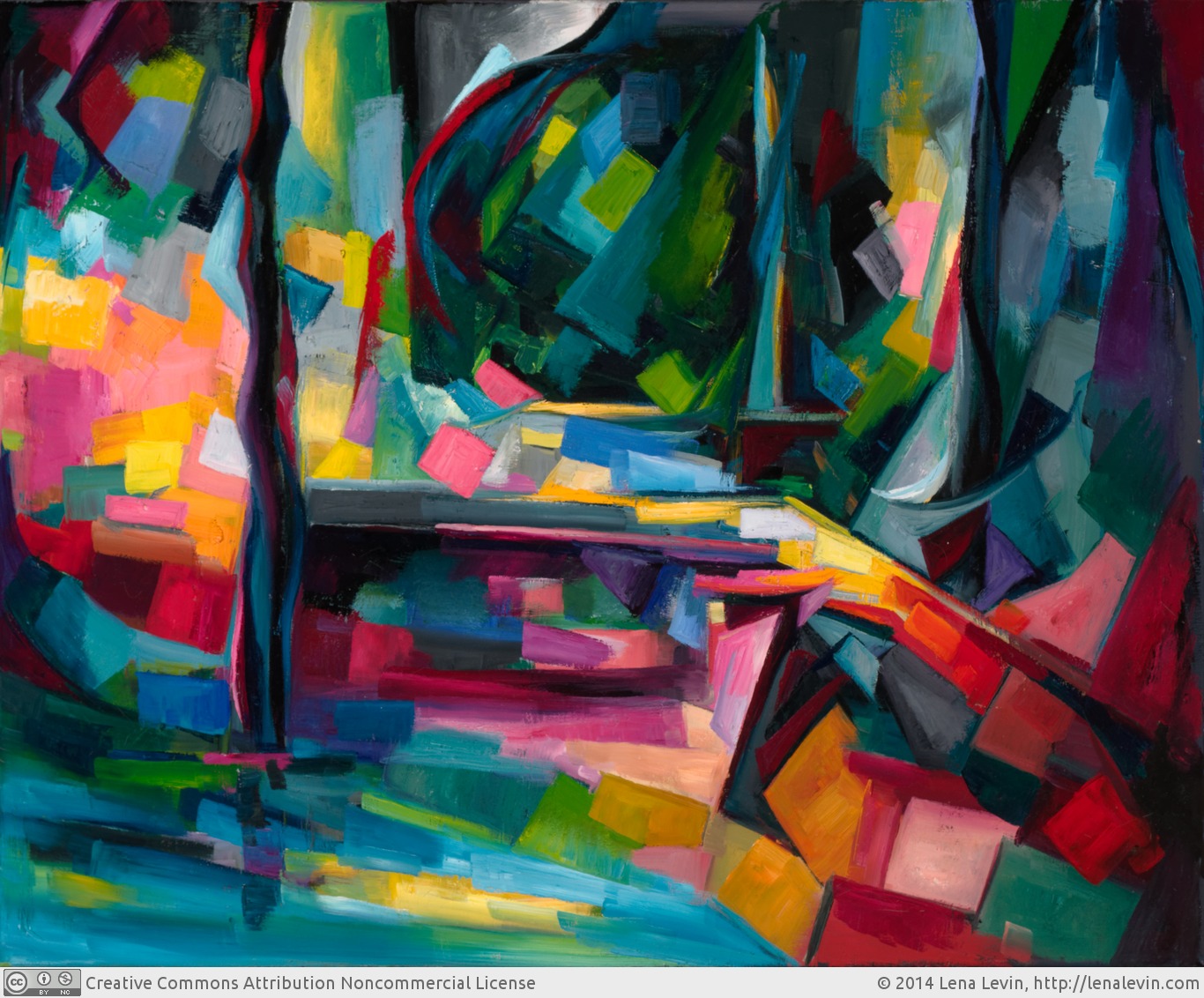

A painting is always in the present, within a single on-going moment in time. One could even say, it is time-less. A modern viewer expects a painting to represent one moment, and the painting opens itself to the beholder as a whole, all at once. The unfolding of this experience in time is entirely up to the beholder (if, indeed, they even care to spare more than a glance for it before passing to the next one).

So, is there Time in painting?

In the golden time of man’s innocence, a painter could rely on allegories, or represent sequences of events within the scope of the same painting: these are essentially literary, story-telling devices of representing Time, beyond the realm of painting per se. Resorting to such devices might have resulted in a successful illustration, but my quest is for translation of sonnets into the language of painting.

I knew that some paintings can change the beholder’s sensation of Time, at least temporarily — just like the subjective sensation of Time often changes “in real life”. Just compare Claude Monet to Paul Cézanne: Monet’s time is as fleeting as it gets (and he fully enjoys the flow), Cézanne’s stands still, like eternity manifested in every single moment. It sometimes seems to me that I wouldn’t even be able to wrap my head around the idea of eternity within now if I hadn’t spent so much time with Cézanne’s paintings.

How does the sensation of Time in painting arise? How is it created? I believe it must be more primal than any concept of Time mediated by language, simply because the way our languages — and our verbal thinking — treat time is based almost entirely on spatial metaphors (Shakespeare, of course, uses a variety of other metaphors for Time, but the spatial ones are unavoidable). When we think about time, we use the way we perceive space and its internal organisation as an explanatory source, as the basis for understanding (or an illusion of it). But the organisation of space is the realm of painting, and no one was better at it than Paul Cézanne.

My pathway to Time in painting had to lie through a study of Cézanne’s space and time, and the first steps on this path are this month’s theme on this blog. If you are interested in this topic, I’d love you to subscribe.

[share title=”If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, please consider sharing it with your friends!” facebook=”true” twitter=”true” google_plus=”true” linkedin=”true” pinterest=”true” reddit=”true” email=”true”]