What is the secret of Cézanne’s Time: its breathtaking stillness, as though eternity was sitting silently right there in the painting? The answer must lie in the way he organises space, because our experience of space is the source for our understanding of time.

There is this immanent tension in painting between two-dimensional picture plane and three-dimensional space. An easy way to describe it would be to say that a painter projects a three-dimensional region of space onto a two-dimensional surface, and faces two opposite challenges: one, more obvious, is to create the illusion of depth and volume, the other is not to “break” the picture plane in the process. Both aren’t really universal — depending on the age and the context, a painter can abandon the illusion of three-dimensionality altogether, or push it to extremes — but Cézanne is a paragon of keeping this tension alive, creating volume and maintaining picture plane at the same time.

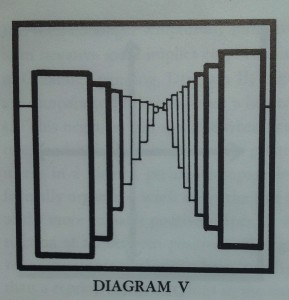

This quality of Cézanne’s composition is at the core of Erle Loran’s classic book on the subject. Here is how he illustrates the challenge:

“Diagram V is a configuration of overlapping planes that recede toward a vanishing point at the horizon. The exaggerated effect of deep space is the result of an uncompensated perspectival convergence and diminishing of sizes. The diagram illustrates what is meant by a funnel effect and a hole in the picture.

“Diagram V is a configuration of overlapping planes that recede toward a vanishing point at the horizon. The exaggerated effect of deep space is the result of an uncompensated perspectival convergence and diminishing of sizes. The diagram illustrates what is meant by a funnel effect and a hole in the picture.

The illusion of space cutting into the picture plane results when no provision for a return out of depth is made. Cézanne never created this kind of effect, and it is intended here as an illustration of a very disturbing and tasteless kind of three-dimensional arrangement” (p. 20).

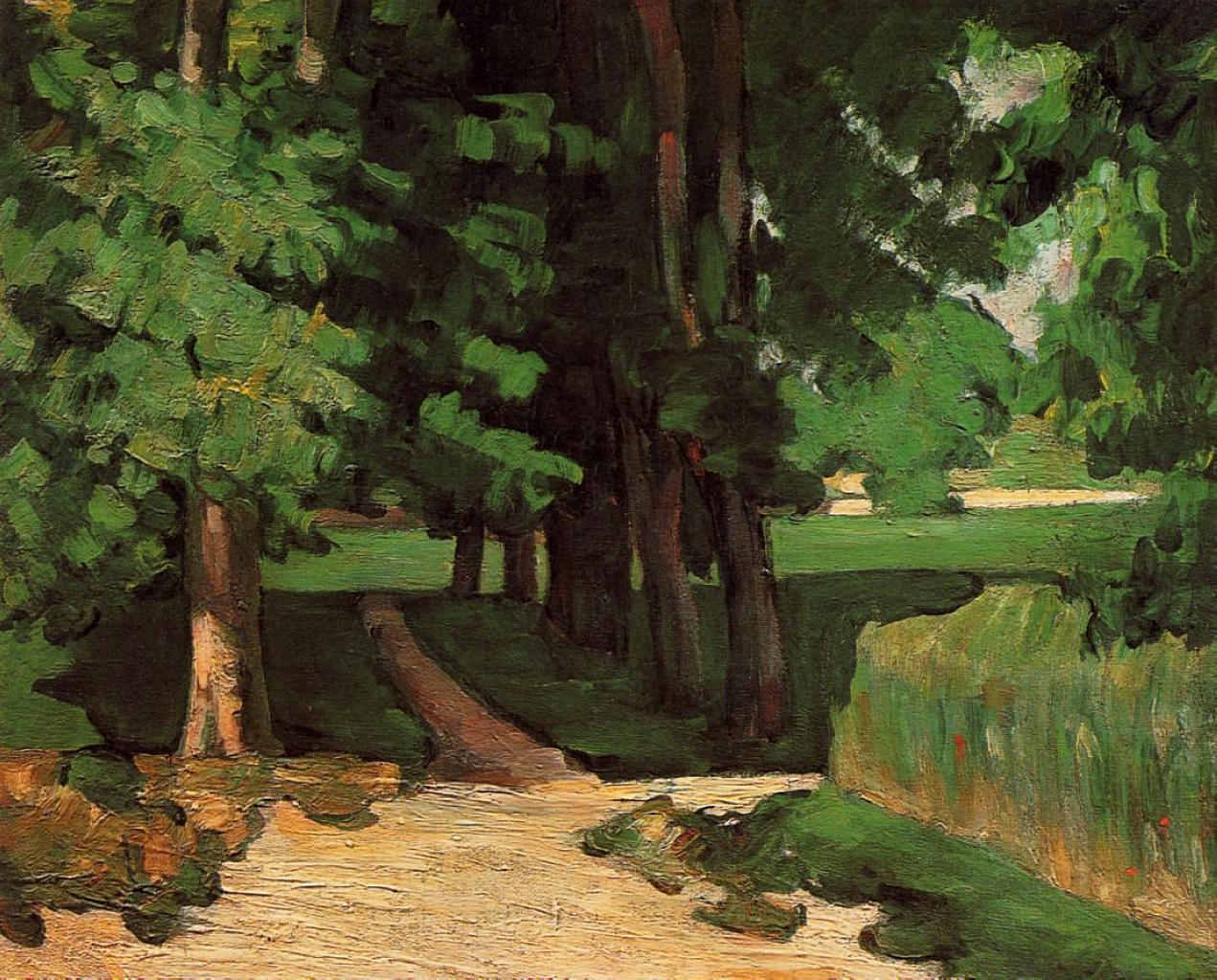

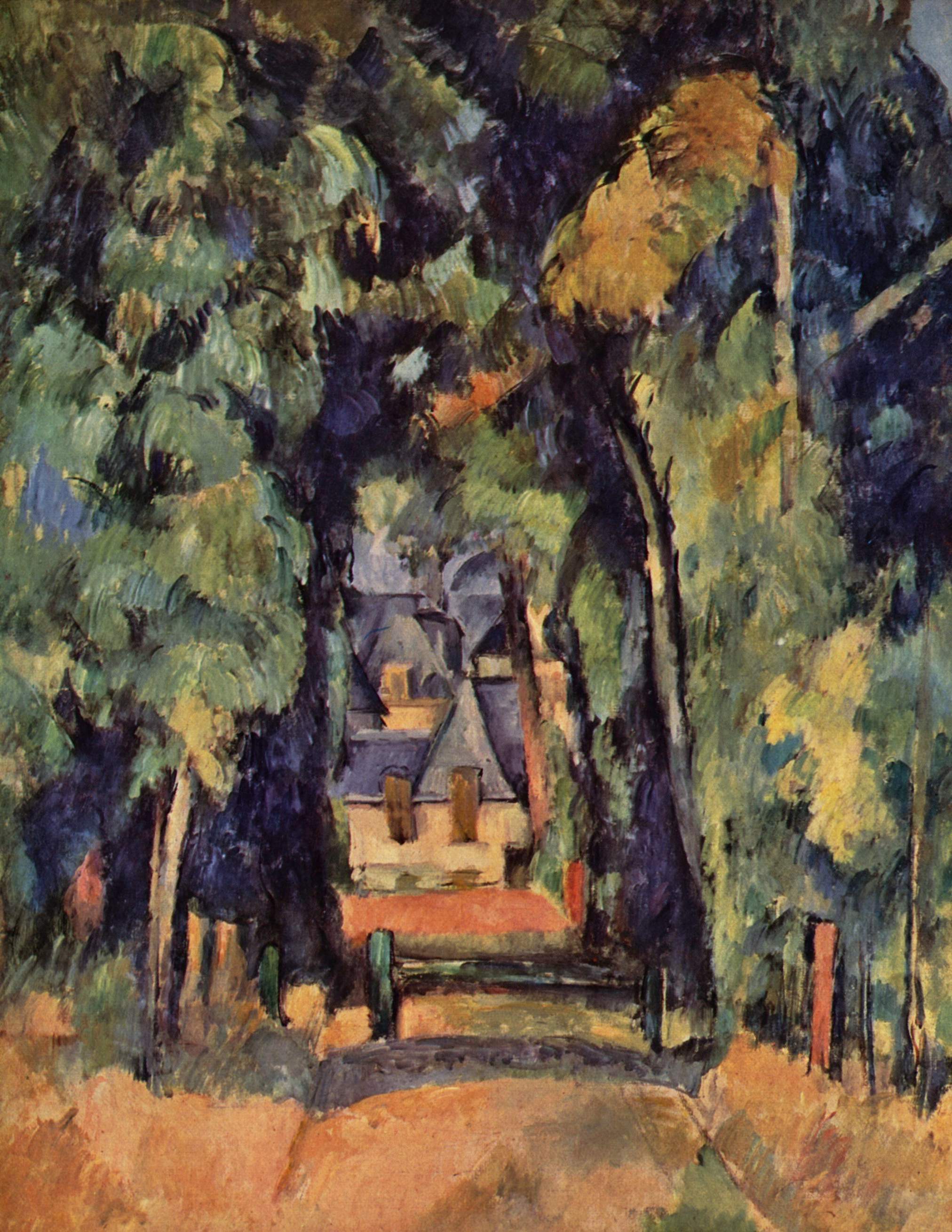

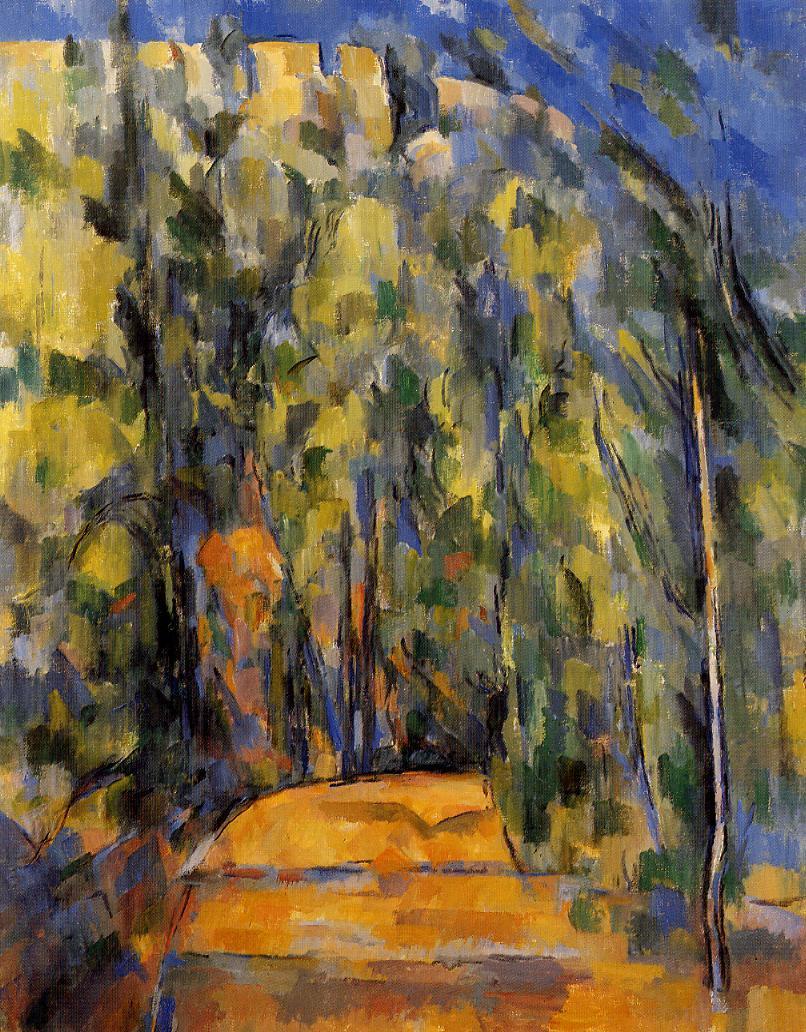

This illusion of “hole” is so easy to create because we are accustomed to “seeing” space extending away from us to (what amounts to) invisible infinity: we know that if things seem smaller and smaller, it means they are more and more distant, and we know that if at some point they become too distant to discern, it doesn’t mean the space ends there; and the brain uses this knowledge to compute the coherent picture it presents to the consciousness. As Loran mentions, Cézanne never lets the beholder fall into this illusion — there are no holes in his picture planes. This post is illustrated by his paintings of alleyways, where the view itself presents the quintessence of the “funnel” challenge, and you can see that, in one or another way, they all do indeed stop this mental motion towards infinite space and return the beholder out of depth.

Erle Loran traveled Cézanne’s country and took photos of the same views — as close to Cézanne’s motifs as he could. One of his goals was to study how Cézanne modified nature to prevent the illusion of the space’s infinite expanse and preserve the essential two-dimensionality of the picture plane. He notices how Cézanne disregards perspective, raises the earth plane to make it “closer” to the picture plane (diagonal rather than horizontal), makes distant objects larger to bring them forward, “turns” the walls of houses and other structural planes (as though different parts of the view are seen from different vantage points).

At first, these observations seemed to me like the answer to my question: that’s how Cézanne changes the space in front of him to create this special sensation of time. Indeed, if the whole infinite expanse of space is brought within the flatter “picture box” and placed between its foreground and background planes, the corresponding sensation of time would bring all eternity within the single moment of now.

But there is something wrong here.

Cézanne’s paintings give an impression of ultimate objectivity — in Rilke’s words, “limitless objectivity, refusing any kind of meddling in an alien unity” (October 18, 1907). In an earlier letter (October 12), Rilke describes his conversation with Mathilde Vollmoeller in front of Cézanne’s paintings; she says: “He sat there in front of it like a dog, just looking, without any nervousness, without any ulterior motive.” As an example of a quite different beholder, about half a century later, here is how Colin Wilson, in “The Outsider”, compares Van Gogh and Cézanne:

“…the difference is more than a difference of technique; it is a completely different way of seeing. Cézanne rendered painstakingly, as Henry James rendered his pictures of European society, with innumerable small brush strokes. The final result has an orderliness that springs out of discipline. From Cézanne’s painting, we learn a great deal about the surface of the object painted and its distance from the eye, and a great deal about the will of the man who was determined to render it fully. We learn nothing of Cézanne’s emotion.”

Again, the distinct impression that we see the objective reality, including the objects’ “distance from the eye” — in an apparent contradiction to Loran’s objective observations. So, is the impression of Cézanne’s limitless objectivity false? Is it just an illusion created by a master painter with clever manipulation of structural planes?

I don’t think so. Rilke and Loran obviously look at Cézanne from very different perspectives — Rilke is a poet, Loran a painter — and Rilke would have probably been the first to defer to a painter’s superior knowledge. But there is one point on which they agree, and it is that Cézanne didn’t have a good conscious access to his insights as a painter (although Rilke talks about it with admiration, and Loran, with a certain degree of frustration), and this means he didn’t manipulate his structural planes with a conscious pictorial intention in mind. Although the desire to learn from Cézanne might seem more obvious in Loran, but it is also present in Rilke — and while Loran was learning to paint, Rilke focused on learning to see. He felt he had a special “private access” to Cézanne’s paintings, because their work intersected at some place where the difference between poetry and painting ceases to matter. He writes:

“It is the turning point in these paintings which I recognised, because I had just reached it in my own work or had at least come close to it somehow, probably after having long been ready for this one thing which so much depends on.”

And it is in this context, in the letter of October 18, 1907, that he mentions Cézanne’s limitless objectivity, refusing any kind of meddling.

What does he mean? The thing is, it’s not quite the case that a painter creates two-dimensional projections of a real three-dimensional space, simply because the images our eyes receive and transmit to the brain for further computing are two-dimensional projections to begin with (in case of landscapes, it’s essentially the same image in both eyes). Just like everyone else, what the painter’s eyes register is a temporal sequence of two-dimensional signals. The difference lies in what happens next.

I touched upon this difference in my post on Claude Monet’s vision: the “normal” process of computing a coherent three-dimensional model of what we see involves a lot of what Eric Kandel, in “The age of insight”, calls “brain’s creativity”. He writes

“A digital camera will capture an image, be it a landscape or a face, pixel by pixel, as it appears before us. The eye cannot do that. Rather, as the cognitive psychologist Chris Frith writes: “What I perceive are not the crude and ambiguous cues that impinge from the outside world onto my eyes and my ears and my fingers. I perceive something much richer— a picture that combines all these crude signals with a wealth of past experience.… Our perception of the world is a fantasy that coincides with reality.””

The assumption that this fantasy coincides with reality sounds somewhat too far-fetched to me, but that’s obviously the same assumption Loran made in his book: he compared Cézanne’s paintings with photos, and with a three-dimensional fantasy created by his own brain (and based on his own past experience), and found that Cézanne modified reality.

But what Cézanne did, I believe, is the opposite: as Rilke intuited, he didn’t let his brain meddle with what he saw in the way people normally do, didn’t let his past everyday experiences interfere between the present visual reality and its painting. Or to put it another way, the decades of painting experiences retrained his brain to see more directly, without reconstructing what the eyes cannot see on the basis of prior “common sense” knowledge or any intellectual conceptions. I believe it is this non-meddling that creates the effects observed by Loran; Cézanne’s painting don’t extend into infinite space behind the background simply because the eyes don’t see that space — it is a fantasy of the brain.

In my experience, the idea of objectivity is often confused in everyday language with what would more accurately be called “common sense”, that is, some sort of coordination between people’s world views: something is objective if everyone can agree on it; if only one person sees things in a certain way, then it surely must be “subjective”. But what if this one person has spent more time and effort cleansing and refining his sense of vision, awakening himself to the visual reality, than anybody else? Wouldn’t it make sense to assume that he sees more clearly and objectively than the rest of us? Obviously, Rilke thought so, and he spared no effort in learning to see from Cézanne:

“When I remember the puzzlement and insecurity of one’s first confrontation with his work, along with his name, which was just as new. And then for a long time nothing, and suddenly one has the right eyes …” [October 10, 1907]

And when one does, one begins to perceive Cézanne’s space in nature, undistorted by any “common sense” human knowledge:

“A large fan-shaped poplar was leafing playfully in front of this completely supportless blue, in front of the unfinished, exaggerated designs of a vastness which the good Lord holds out before him without any knowledge of perspective.” [October 11, 1907]

[share title=”If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, please consider sharing it with your friends!” facebook=”true” twitter=”true” google_plus=”true” linkedin=”true” pinterest=”true” reddit=”true” email=”true”]