My tongue-tied Muse in manners holds her still,

While comments of your praise richly compiled,

Reserve thy character with golden quill,

And precious phrase by all the Muses filed.I think good thoughts, whilst others write good words,

And like unlettered clerk still cry ‘Amen’

To every hymn that able spirit affords,

In polished form of well-refined pen.Hearing you praised, I say ”tis so, ’tis true,’

And to the most of praise add something more;

But that is in my thought, whose love to you,

Though words come hindmost, holds his rank before.Then others, for the breath of words respect,

Me for my dumb thoughts, speaking in effect.William Shakespeare. Sonnet 85

… the sonnet is a painfully precise description of my own perception of my life as an artist, coloured and shaped by acute awareness of its overwhelming context: the long history of art, the sky-scraping mountains of books already written and paintings already painted.

May 25, 2016: Golden and Blue

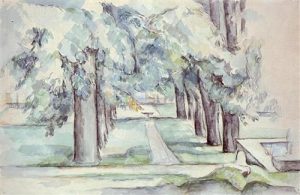

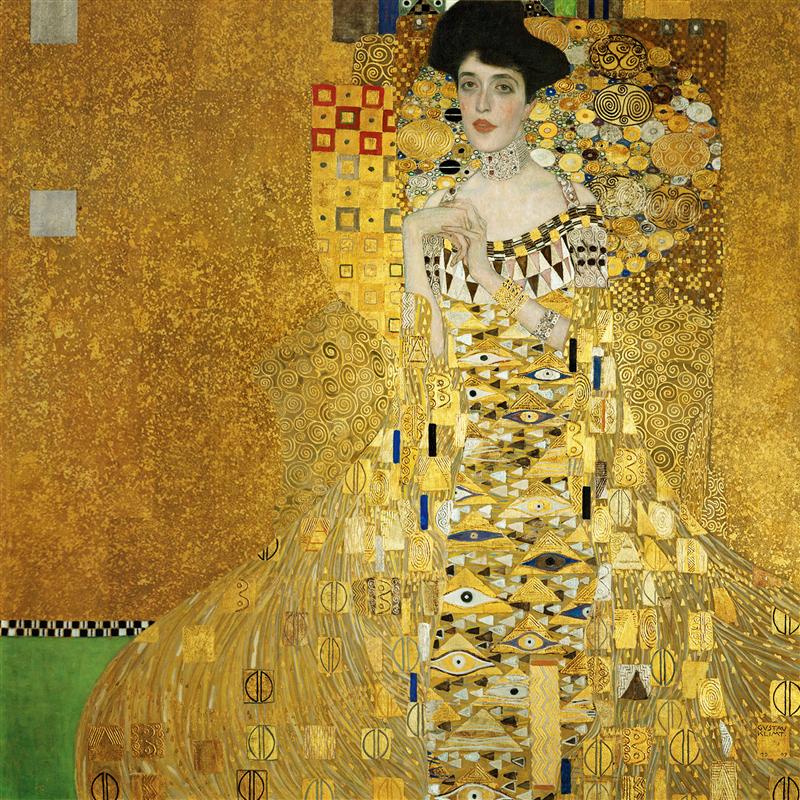

The painting began with a glimpse of colour contrast, “golden” versus “blue”, as an expression of the tension between polished, well-refined comments and dumb thoughts. This contrast, yellow versus blue stands for light versus dark, visible versus invisible, material versus spiritual, outer (apparent) versus inner (real). Kandinsky writes about this range of associations in “Concerning the Spiritual in Art”, but there is also a link to how Paul Cezanne started his paintings, his first grey-blue compositional lines — so blue becomes the colour of unexpressed, under-developed thought.

May 26, 2016: Colour Charts and Ornaments

The golden versus blue idea was a starting point for the colour chart for this painting. I originally thought of these charts as a way of figuring out the colour harmony of the painting; now, I do this rather as form of more active, visually focused mode of meditation. It’s a way the create a (mental) space for the future painting to show up.

The golden versus blue idea was a starting point for the colour chart for this painting. I originally thought of these charts as a way of figuring out the colour harmony of the painting; now, I do this rather as form of more active, visually focused mode of meditation. It’s a way the create a (mental) space for the future painting to show up.

The compositional idea clarified itself in the process: the golden areas of picture plane are more ornamental, more refined, almost like a golden frame, enclosing and constraining the rougher, more sketch-like, less expressed bluish areas.

It also brought in two other painterly associations: Picasso’s “Queen Isabel”, with its play on flatter ornamental areas, and Klimt’s golden ornamental backgrounds. But I still don’t see the subject matter of the future painting, nor is there any real inner opening to the sonnet. No emotional connection strong enough to form the seed of a painting. I am still on the surface of the sonnet, not within.

May 27, 2016: Painting from Life and Dutch Flowers

A pause in the study of the sonnet. There was an overwhelming sensation of life’s bleak meaninglessness the night before, hence the urgent need just to paint from life — doesn’t matter what, just about anything, simply to reconnect with life. Yes something from the sonnet process transferred into this painting (“Window”) — the contrast between expressed and under-expressed, refined and rough.

Contrary to all conventional advice, the vantage point here doesn’t allow for the illusion of seeing the whole scene at the same time: I couldn’t see the still life on the windowsill and all areas of the landscape outside with one glance. There is an eye movement within this painting; it is a kind of “quilt” made from different paintings, different areas of the scene seen and painted separately.

This quality reminded me of the “Dutch flowers” exhibition we saw a couple of weeks back in London. It was perhaps the first time I paid real attention to this genre; I used to perceive it as very alien, way too decorative, too well-refined, too polished. There is a conspicuous association with this want to distance oneself from others’ words in Shakespeare: polished, over-expressed, overly refined and richly decorative. But there is also another connections: these floral scenes, presented like bouquets to the unknowing eye, were often composed of flowers from different seasons — flowers which couldn’t be possibly present within a single bouquet. They couldn’t be seen at the same time, in juxtaposition to one another, except in a painting. So there is a hidden “patchy” quality to these paintings. They are also quilt-like, albeit in a completely different way from mine.

May 31 — June 1: My tongue-tied Muse

Over the weekend, the subject matter of the future sonnet painting emerged, almost without me noticing it: yellow, golden-coloured roses. I bought a bunch of them on Sunday, to paint the sonnet from life.

This choice of subject matter seems random: what does it have to do with the young gentleman to whom the sonnet is addressed? The idea of flowers is probably connected to the Dutch flowers. This association has still a more important part to play in the emergence of this painting. But more generally, flowers — and roses in particular — seem to be one the running theme of the series; this motive is evidently anchored in the sonnets sequence as a whole.

More importantly, though, this sonnet, like many others, calls for re-interpreting its addressee as something more like Universe as a whole — everything in reality, not just one particular person. There is no way for me to find an inner opening to the sonnet without this expansion of its “you”, to align my experience of the world — the narrow keyhole (using Kafka’s expression) through which I see it — with the keyhole offered by the sonnet. Come to think about it, expanding the “you” of the sonnet to the universe as a whole might be closer to its inner meaning than imagining any one individual person as its “you”.

This opening — the inner connection to the sonnet — finally emerged only during the first day of painting. I had to start painting with only a vague idea of what I am doing, but in the process, I suddenly realised that the sonnet is a painfully precise description of my own perception of my life as an artist, coloured and shaped by acute awareness of its overwhelming context: the long history of art, the sky-scraping mountains of books already written and paintings already painted.

My tongue-tied Muse in manners holds her still. I am constrained into “manners” (and, quite often, into silence) by everything that has already been painted and written, by the knowledge that there are already enough words and enough paintings in the world — much, much more than any human being can read and see in a lifetime. It does indeed feel exactly like this: all one can do to express one’s own thoughts is cry “Amen” to others, like an unlettered clerk. After all, what is this whole “Sonnets in colour” series if not such an “Amen” (sort of)?

This clarified meaning brought into the painting a “quote” from one of Jan Davidsz. de Heem’s decorative florals: two pinkish buds in the left bottom corner, and the glass vase. They stand for — or point to — the well-polished, golden, richly compiled refinement of “other”. The constraining “frame”, within which my rough, under-expressed painting from life (one’s own dumb thoughts) is enclosed, turned into a circle — another, more abstract compositional quote from de Heem.

This quote — combining as it does flowers separated by centuries as though within a single bouquet — was needed in the painting, but it modified and largely obscured the original contrast between “golden” refinement and “blue” sketchy outline; the painting became more complex, and the contrast between “words” and “thoughts”, more multi-dimensional and, for the time being at least, less clear.

June 2: Contrasts and unity

The next painting session was about clarifying and strengthening these contrasts: clarifying colours and the ornamental quality of the right-most rectangular area of picture plane, tightening and refining the flowers quoted from de Heem, and changing the yellow roses in the upper left corner into something more abstract, non-representational, un-expressed.

As always the case with paintings focusing on “internal” stylistic contrasts, the challenge is to make these contrasts clear while keeping the whole composition stylistically unified nonetheless. On another level, this is the challenge of trying to combine pointers to reality and reality itself within the same artwork.

June 3: Final Notes

The last, very slow, painting session; further clarification and tightening of contrasts and details. The last touches, the last steps are always the hardest and the slowest.

I posted an in-progress photo on Google+, and Terrill Welch’s comment about unusually “circular” and softer brushwork gave me the idea of strengthening this additional contrast, the contrast between smoothness and “roundness” of refined expression and rectangular roughness of “dumb thoughts”.

I am almost sure there will be a return to some areas later on (especially in the context of the overall nine-sonnets composition), but for now, I am leaving the painting be.

Just like there is an arc, a curve in the process of painting each individual sonnet, there is probably a similar (albeit much longer) U-like curve to the whole “Sonnets in colour” series. If so, this painting — or may be this whole composition (“Poet and Muse”) — feels like the deepest, the lowest segment of this “U”. The months spent painting these sonnets were filled with all kinds “negotiating” my own place in the world, and the place of my work — with myself and with my Muse. At some level, this sonnet feels like a culmination of these negotiations.

Or maybe I am just fooling myself — entertaining the hope that the curve will go upwards from here, that it will be easier from now on.