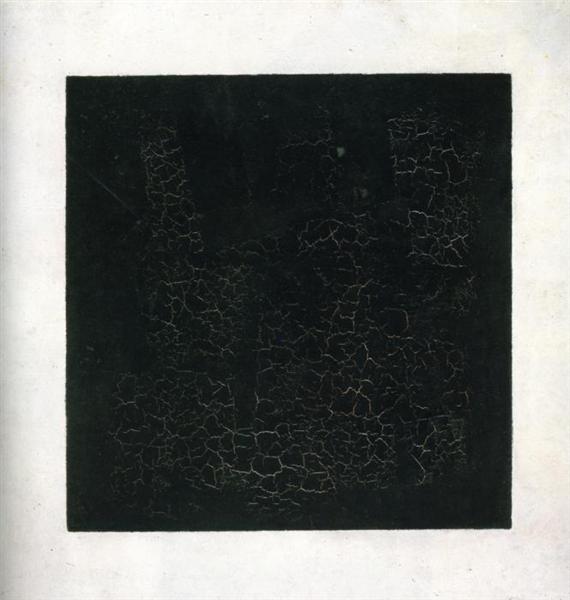

It hit me ten days ago, while painting in the studio, that Kazimir Malevich’s “Black square” (1915) represents the death of painting. A huge fat full stop in its evolution.

I have always hated this painting. It is, of course, not unique in representing the death of painting, but it seems to do so in the purest, clearest, inevitable form. I remember a friend of mine weeping uncontrollably in front of this painting in George Pompidou Centre in Paris, as though at a funeral of someone she used to love. And my own feeling of detached alienation — in contrast to her, I didn’t want, I couldn’t let it in.

I guess I never wanted to accept that this painting, and the end it represents, are both logical and inevitable. But now there is no other way for me to go any further.

I think this change must have been brought about by reading and re-reading Gottfried Richter’s “Art and Human Consciousness”. In this book, he presents a grand story of visual art as both a manifestation and a driving force of the transformation of human inner experience of reality, from Ancient Egypt till the first part of the twentieth century.

Painting appears in this story relatively late, when it detaches itself from architecture as an independent art form. This separation itself is part of the history-long movement from huge to small, and from “outer” to “inner” experience of reality. For Richter himself, this represents a movement of the Divine from being “out there”, in the non-human cosmos, inward, into the inner world of human beings — and the crucial point in this movement is, of course, the death and resurrection of Christ. But the “hard facts” of this story are all about the human experience of reality and its visual representation in art: they don’t really depend on religious interpretation.

In painting, this movement from “outer” to “inner” shows up as the path leading from grand historical and biblical motives — through the human, earthly visual reality of portraits, landscapes and still lifes — and then, ultimately, to abstraction, as an attempt to represent feelings in a way completely independent from the outer “world of visible things” (this was Malevich’s conscious intent in his “suprematism” paintings, like “Black square”).

And it is by no means an accident that this powerful urge in visual art to withdraw completely from the visual reality happens simultaneously with Freud’s invention of the “ego”, and its ultimate world-alienation.

But a complete withdrawal from sensory reality of life is death, there is just no way around it, no other name for it. And for painting, the withdrawal from visual reality is the ultimate contradiction: after all, it cannot help but appeal to the viewer’s sense of vision, and it’s hard to do that while simultaneously rejecting one’s own sense of vision as a valid window to reality.

And so we find ourselves in the after-life of painting, which seems to go on, in spite of everything, due to our unquenchable inner need to paint.

Is it a resurrection? I don’t know.