Frank O’Hara: Why I am not a painter

I am not a painter, I am a poet.

Why? I think I would rather be

a painter, but I am not. Well,for instance, Mike Goldberg

is starting a painting. I drop in.

“Sit down and have a drink” he

says. I drink; we drink. I look

up. “You have SARDINES in it.”

“Yes, it needed something there.”

“Oh.” I go and the days go by

and I drop in again. The painting

is going on, and I go, and the days

go by. I drop in. The painting is

finished. “Where’s SARDINES?”

All that’s left is just

letters, “It was too much,” Mike says.But me? One day I am thinking of

a color: orange. I write a line

about orange. Pretty soon it is a

whole page of words, not lines.

Then another page. There should be

so much more, not of orange, of

words, of how terrible orange is

and life. Days go by. It is even in

prose, I am a real poet. My poem

is finished and I haven’t mentioned

orange yet. It’s twelve poems, I call

it ORANGES. And one day in a gallery

I see Mike’s painting, called SARDINES.

What makes us what we are?

Why am I a poet and not a painter? — asks Frank O’Hara in this poem. I’d rather be a painter…

But what kind of answer is possible here? It’s obviously not about some deliberate, conscious decision — free will or not, one doesn’t really get to choose what they are. The only marginally answerable re-wording of this question would be something like “What is it in my inner make-up, in the way my perception and cognition work, that makes me a poet, and not a painter?”

And that’s the question O’Hara seems to have had in mind. At least his answer — if it is an answer — comes in the form of two short stories, one about the process of painting, the other about the process of writing a poem. And there seems to be a clear difference in underlying cognitive processes:

- The painting starts with a thing (“It needed something there”— says the painter; something = some thing) and transforms into an abstraction, because the thing was “too much”.

- The poem starts with an abstraction — a thought about colour — and transforms into pages of words (in prose), much more descriptive than the painting. Here is the beginning of these poems, “Oranges”:

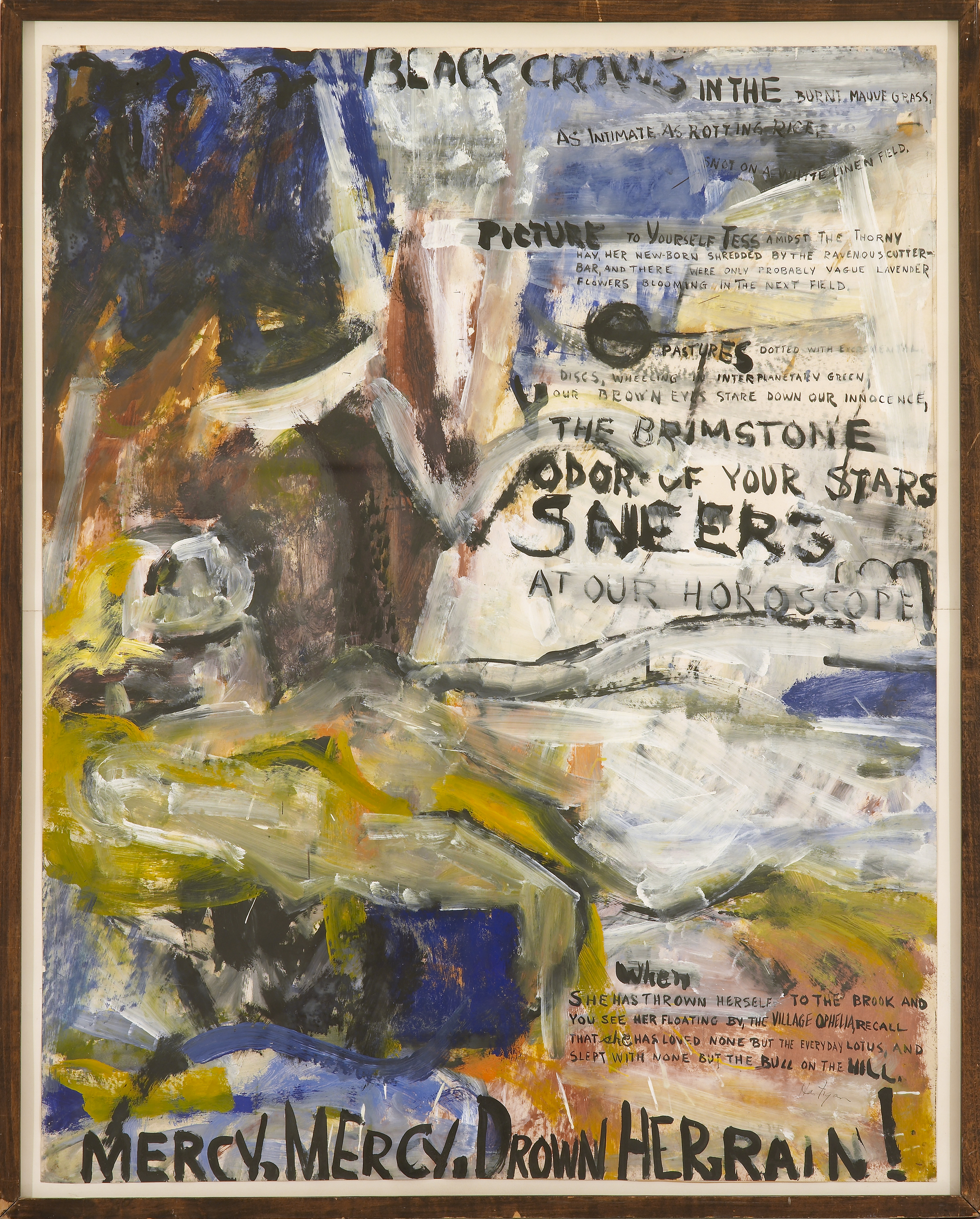

“Black crows in the burnt mauve grass, as intimate as rotting rice, snot on a white linen field.”

Quite a lot of things — which are, in some mysterious ways, generated by the thought of “orange”. Perhaps as mysterious a transformation as the transformation of sardines into a flurry of colours in Goldberg’s painting:

The painter starts with the image of a thing and transforms it into colour because the thing “was too much”; the poet starts with the idea of colour and transforms into words, because “there should be so much more, not of orange, of words, of how terrible orange is and life”. Orange is never enough for a poet, sardines are too much for a painter.

Is this the answer to the initial question? In a sense, yes, but not quite. The poem is more complex than that, and the complexity resides in how these two little stories fit together.

Both stories — the one about the painter, and the one about the poet — are written (mostly) in the characteristic, and overly simplistic, “I do this, I do that” style, in a mixture of simple present and continuous present tenses. This makes it seem as though the second story followed the first in the real-life unfolding of the events.

But this is not really the case: the poem, “Oranges”, was written in 1949, and the painting, “Sardines”, was painted in 1955. But there is a connection — beyond the mere contrast of cognitive processes; it might be invisible in the poem, but it’s obvious once you see the painting. This painting’s colour harmony is orange-y: mix all its colours together, and you’ll end up with orange. It is this colour that connects the first story to the second, as though it’s Goldberg’s painting that inspired O’Hara’s thinking about orange. Not in the realm of real time-space (where it might well have been the other way round), but in the internal logic of the poem itself: after all, O’Hara could have chosen any of his poems to compare the processes. I believe it’s the colour: orange that led him to recall this particular one (or rather a series of twelve, as it happens).

And this creates a kind of semantic circle, which belies the overt simplicity of this poem’s structure: the painting follows the poem in “real life”, but invokes it within the logic of this poem.

And there is another circular movement which replaces the logical, narrative one. This is not mentioned in the poem, but the second story, the story of “Oranges” has a real-life painting-related sequel: in 1952, another painter friend of O’Hara’s, Grace Hartigan, painted a corresponding series, also entitled “Oranges”, incorporating O’Hara’s words into the paintings. So there was a painting process directly inspired by the poem.

But the poem ends quite differently, with O’Hara seeing Goldberg’s painting in a gallery. It is entitled “Sardines”, even though there are no more sardines in it, just like the poem is called “Oranges”, in spite of having no oranges in it. Both the poet and the painter retained the original “source” of the work in the title, even though it had as well as disappeared in the process. The poem circles back to where it started — to disappearing sardines, and concludes itself with a similarity between two processes, not with the contrast which might explain why the poet is not a painter. Instead, the two processes emerge almost as two sides of the same one, two different views of the same phenomenon.

Since my fun in this life is (mostly) in painting poems, how could I resist the temptation of responding to this poem “in kind” — by a painting entitled “Why I am not a poet?”. I honestly believe the answer given by this painting is about as clear as the answer given by the poem. At least to me it is…