The letting go is a real death, a real dying; it costs us an enormous amount of energy, the price, as it were, which life exacts from us over and over again for being truly alive.

Brother David Steindl-Rast

June 29, 2016

Something huge — and very scary — happened while I was meditating this morning.

It began as a sensation of enlightenment, literally: a dissolution of the self into something that felt like pure light. The thought that followed was that, contrary to what I wanted to believe, my life’s purpose — the source of its meaning — is not in painting per se, but something beyond that, something different.

The thought felt like an “aha-moment”, because it clarified — in retrospect — lots of murky, ambiguous sensations and events of the last days, weeks, and maybe even months. And, at the same time, it was scary, big-time scary — because I don’t want to abandon painting. I am scared to let it go, because that’s what makes me feel alive.

In the studio, while painting the eighty seventh sonnet, I realised the connection. I have known for a while that this new composition, the one starting with this sonnet, is about the paradox of letting go. I had long since accepted that this series does things to me, that it is not really separate from my life — so I had a premonition that I would have to let go something huge in the process. I just didn’t think, not for a moment, that it would be painting.

July 3, 2016

I woke up in the middle of the night, and stayed awake for about two hours, meditating, doing my best to listen to what’s going on inside me.

And I understood more about this thing-beyond-painting, the glimpse of which I had in meditation a couple of days ago. It has to do with witnessing and (self)-examining the process of painting: contemplating this process “from the inside”, from within the experience, from the inner space of painting.

This brings together my two “projects”, which have been pulling me, painfully, in two different directions, “Sonnets in Colour” and “Art of Seeing”. Or so it seemed. Now, they feel rather like two pillars of the same meaning, or two sides of the same process.

This is a liberating insight. It intensifies the feeling of meaningfulness and freedom, but there is a catch.

I had to let go of the idea of “being an artist”, let go of painting. It doesn’t mean quitting painting, this letting go in the Buddhist sense: setting painting free, releasing attachment. But it was incredibly hard to do, and incredibly scary: I so don’t want to lose painting, I really need it to be alive. But I knew I had to do it, and I so I did — trying to comfort myself with the thought that you can only lose what you have never had.

July 4, 2016

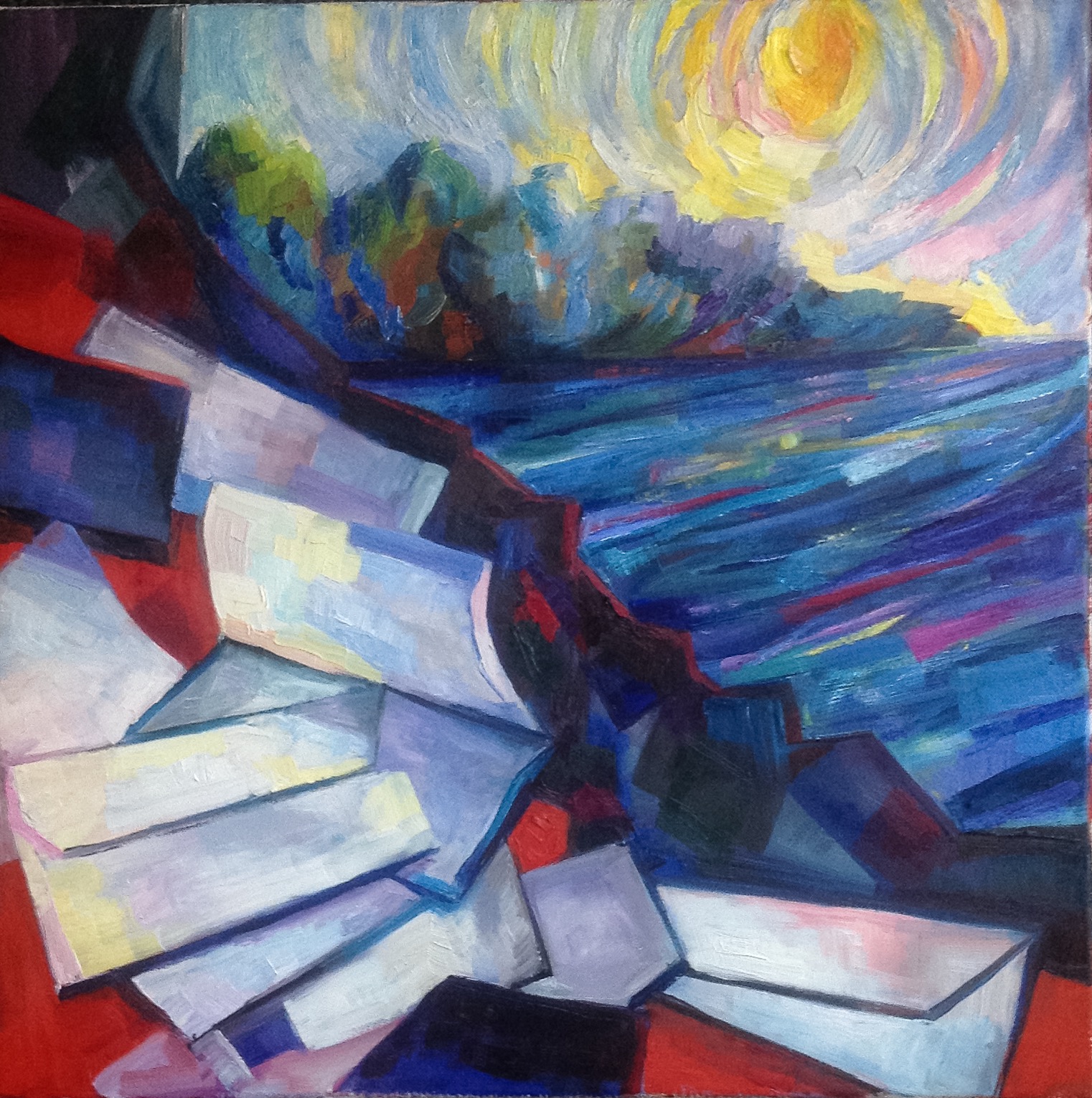

The first painting session after the letting go experience the night before: I returned to the preliminary study for Sonnet 87, “Still life with check book”. I left it alone a couple of weeks ago, because it fulfilled it’s “study” purpose: I understood, or thought I understood, how I need to paint the still life part of the sonnet painting.

Why I returned to this painting?

One reason is a vague sense of dissatisfaction with the current stage of the sonnet painting itself. On the other, there seemed to be a potential in this smaller painting: it could be more than it currently was.

From the impressionistic study, it wanted to move towards something more “analytical”: analytical cubism, or Filonov’s “analytical realism”. There is something in painting wallets and check books as quasi-aesthetic objects — something more than I have achieved so far. And the still life setting was still there in my studio, since it played a role in the sonnet painting, too.

I approached the painting with the intention, a request to myself, to “channel” the experience of analytical cubism. In the process, it transformed into a return to the long-running motive of “colourful cubism”, the quest to reconcile these opposites. There was also a palpable influence of having spent two last weeks with Matisse’s remake of de Heem’s “A table of desserts”: the painting moved in the direction of dark versus light contrasts distributed all over the picture plane. The underlying inner experience is an experience of separation. This painting day “flattened” the pictorial space (as expected from the “cubist” approach), but also “broke” the picture plane (in defiance of cubism).

July 5, 2016

There was an Awakin Weekly letter in my inbox this morning, with an excerpt from an old essay by Brother David Steindl-Rast. He writes:

This inner gesture of letting go from moment to moment is what is so terribly difficult for us; and it can be applied to almost any area of experience. […] The letting go is a real death, a real dying; it costs us an enormous amount of energy, the price, as it were, which life exacts from us over and over again for being truly alive. For this seems to be one of the basic laws of life; we have only what we give up.

This is a better description of these last few days than I could write myself.