What are we made of?

This diptych of sonnets, forty forth and forty fifth, is a fusion of two answers to this question — answers which seem like they come from two different worlds.

[accordion][accordion_item title=”Sonnet 44“]

If the dull substance of my flesh were thought

Injurious distance shouldn’t stop my way,

For then despite of space I would be brought

From limits far remote where thou doth stay

No matter then although my foot did stand

Upon the farthest earth removed from thee,

For nimble thought can jump both sea and land

As soon as think the place where he would be.

But ah, thought kills me that I am not thought

To leap large length of miles when thou art gone,

But that, too much of earth and water wrought,

I must attend time’s leisure with my moan.

Receiving naught from elements so slow

But heavy tears, badges of either’s woe.

[/accordion_item]

[accordion_item title=”Sonnet 45“]

The other two, slight air and purging fire,

Are both with thee, wherever I abide;

The first my thought, the other my desire,

These present-absent with swift motion slide.

For when these quicker elements are gone

In tender embassy of love to thee,

My life, being made of four, with two alone

Sinks down to death, oppressed with melancholy;

Until life’s composition be recured

By those swift messengers returned from thee,

Who even but now come back again, assured

Of thy fair health, recounting it to me:

This told, I joy; but then no longer glad,

I send them back again and straight grow sad.

[/accordion_item][/accordion]

Shakespeare begins with a dream all too easy to co-feel for anyone who has lived through what is now called “long-distance relationships”:

If the dull substance of my flesh were thought

Injurious distance shouldn’t stop my way…

Wouldn’t it be just glorious if we could travel as fast as our thoughts can:

For nimble thought can jump both sea and land

As soon as think the place where he would be.

A familiar experience, isn’t it: our thoughts easily, and with supernatural velocity, carrying the mind wherever it wants to go, quite unconstrained by dull physical limits. If only our whole bodies could do the same — if only teleportation were possible…

So here we have our first answer: our life is made of thought and flesh, mind and matter — the fundamental duality of human condition.

It may not be an ultimate scientific truth, but it is something that we seem to have a direct, everyday, experience of: I have thoughts, and I have flesh; I experience myself as a mind in a body — and for all I know, this is generally how modern people experience themselves, give or take. It seems like a fundamental property of our worldview — shared, it would seem, by Shakespeare.

But not quite, because there is the second answer — it is brought into the poem by mere mention of sea and land, which immediately transform into earth and water:

… too much of earth and water wrought,

I must attend time’s leisure with my moan.

Here earth and water are two of the four fundamental elements of life, or roots, along with fire and air — which make their appearance in the beginning of the forty fifth sonnet:

The other two, slight air and purging fire,

Are both with thee, wherever I abide;

The first my thought, the other my desire,

These present-absent with swift motion slide.

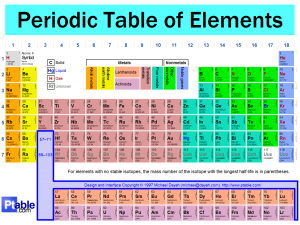

So humans, just like everything else, are composed of earth, water, air and fire. In contrast to the flesh and thought answer, this ancient idea (traced back to Empedocles, a fifth century BCE Greek philosopher) may sound quite bizarre to the modern ear — at least to a Western one (an Eastern one may just notice that the fifth element is lacking, or that the elements are not quite right). We no longer think of the world, let alone ourselves, as being composed of these elements; and they aren’t even elements anymore — we have a whole periodic table instead, and beyond that, all those fascinating particles of the modern physics.

So humans, just like everything else, are composed of earth, water, air and fire. In contrast to the flesh and thought answer, this ancient idea (traced back to Empedocles, a fifth century BCE Greek philosopher) may sound quite bizarre to the modern ear — at least to a Western one (an Eastern one may just notice that the fifth element is lacking, or that the elements are not quite right). We no longer think of the world, let alone ourselves, as being composed of these elements; and they aren’t even elements anymore — we have a whole periodic table instead, and beyond that, all those fascinating particles of the modern physics.

In spite of this, the imagery still works within the domain of poetry — a space protected as it were from the changing challenges of our scientific worldview. We hear these words as metaphors — and these are strong and very intuitive metaphors: even now, with the underlying theory all but forgotten, we still see that fire and air are “quicker” than earth and water, and that desires are rather like fire than like earth, and that life would sink to death without air and fire. But in Shakespeare’s time, this theory was science as it were — and the foundation of their understanding of human condition, both in medical practice and in psychology.

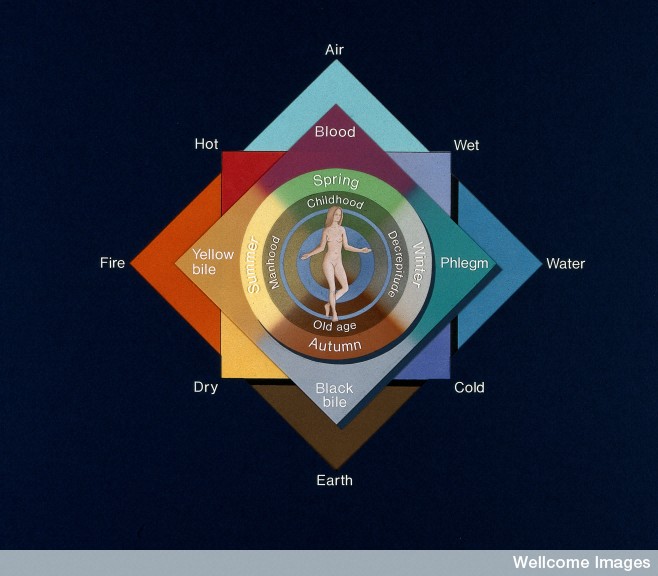

The theory of “four humours”, first introduced by Hippocrates (ca. 450–370 BCE), was very much in vogue in Shakespeare’s time (and influenced medical practice for quite some time afterwards). The “four humours” were thought of as four bodily fluids (black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood), but they were supposed to correspond to the four “elements of nature”. To be more precise, the humours themselves were composed of two elements each (for instance, the black bile was air plus water) — there is a remarkable resemblance, in fact, to the Ayurvedic teachings (emerged at about the same time), where the “humours” (called doshas) are also composed of two elements each. And similarly, health was assumed to depend on all the elements being in some sort of balance, and that was what the various cures (like blood-letting) were aiming at.

![By ABenis at en.wikipedia [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons"](http://sonnetsincolour.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Lavater1792.jpg)

What is really important about this theory — but hard to “get”, looking from our age of fully internalised mind-body divide — is that the “four humours” didn’t belong to either side of this divide: they were both “mental” and “bodily” at the same time. In fact, we know them somewhat better in their purely psychological guises of “four temperaments” (melancholy, sanguine, choleric, and phlegmatic) — even though this classification, too, seems to have been rejected in the modern psychology. The crucial point is, it’s not that a melancholy disposition, or an excess of melancholy, was explained as resulting from out-of-balance “black bile”: the “black bile” and “melancholy” were the same thing (“melancholy” is “black bile” in Greek). In a sense, the state of mind is the state of the body, and vice versa.

That’s why this ancient theory wasn’t a particular favourite with the Christian Church in medieval times — because of this glaring contradiction with the basic Christian distinction between body and soul; but it served as the starting point for the Western medicine during the Renaissance. Here is what one finds on the National Library of Medicine website about medical views in Shakespeare’s time:

During the Renaissance and early modern periods (ca. 1350–1650), most practicing physicians and medical writers continued to understand health and illness within the framework handed down to them by their ancient and medieval predecessors. Medieval representations of the humoural perspective circulated widely in the Renaissance period, book publishers produced attractive editions of Hippocrates’ and Galen’s works, and Avicenna’s Canon continued to enjoy great success as a textbook well into the seventeenth century.

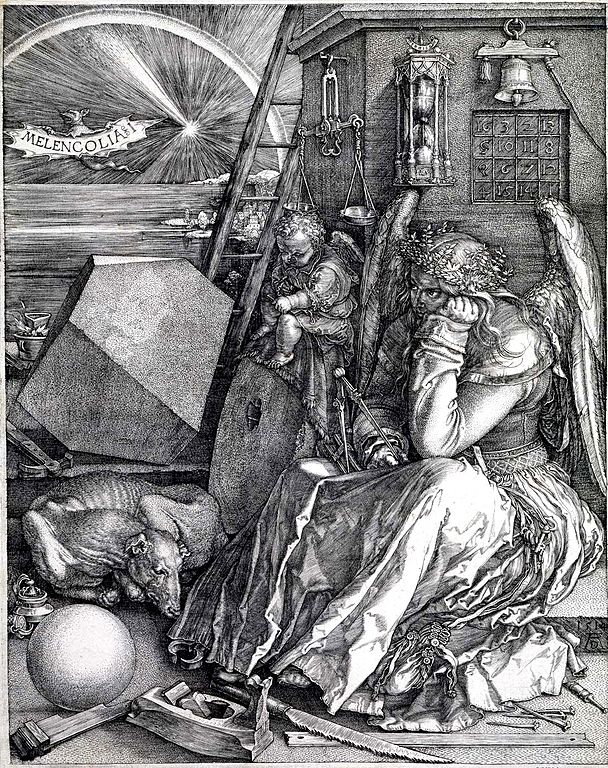

So for Shakespeare, these were not “just” poetic metaphors; the theory of four humours was very much part of his worldview — and his understanding of psychology, which thoroughly informed his plays. Apparently, he was most interested in melancholy: from Open Source Shakespeare, one can learn that he used this word seventy times — compared to ten for choleric, five for sanguine, and a mere one for phlegmatic.

But the forty fifth sonnet doesn’t quite follow the theory: according to the theory, melancholy is composed of water and air, whereas water and earth combined give phlegm. And yet Shakespeare writes:

For when these quicker elements are gone

In tender embassy of love to thee,

My life, being made of four, with two alone

Sinks down to death, oppressed with melancholy;

Is it just because being phlegmatic isn’t really an appropriate state of mind for a lover seized with longing for his beloved — and so his melancholy, in contradiction to the theory, is composed of water and earth?

Not quite, it seems: the ultimate reality of his sadness isn’t in the exact identity of remaining “elements”, nor even in his separation from his beloved — but in the separation between thought and flesh, which violates life’s composition:

Until life’s composition be recured

By those swift messengers returned from thee,

Who even but now come back again, assured

Of thy fair health, recounting it to me:

This told, I joy; but then no longer glad,

I send them back again and straight grow sad.

The cure, the forty fifth sonnet seems to suggest, comes not from the body following the mind to where the beloved is, and not even from the beloved’s own return, but just from the lighter elements, fire and air, returning to join the heavier elements, water and earth — or, in other words, from thoughts being reunited with flesh, the mind returning to its body.

As we would probably say now, from being present here and now.

[share title=”If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, please consider sharing it with your friends!” facebook=”true” twitter=”true” google_plus=”true” linkedin=”true” pinterest=”true” reddit=”true” email=”true”]