If the dull substance of my flesh were thought

Injurious distance shouldn’t stop my way,

For then despite of space I would be brought

From limits far remote where thou doth stay

No matter then although my foot did stand

Upon the farthest earth removed from thee,

For nimble thought can jump both sea and land

As soon as think the place where he would be.

But ah, thought kills me that I am not thought

To leap large length of miles when thou art gone,

But that, too much of earth and water wrought,

I must attend time’s leisure with my moan.

Receiving naught from elements so slow

But heavy tears, badges of either’s woe.

William Shakespeare. Sonnet 44

[line]

Where does landscapes’ power to touch our emotions come from — beyond the pure enjoyment of beautiful or exotic views, or comforting peacefulness of green pastures?

Painting this sonnet has given me a novel way of looking at this question, because the sonnet connects so sublimely sea and land — as elements of a landscape, and water and earth — as fundamental elements of life’s composition: the speaker’s woes, and the dull heaviness of his tears, are made of exactly the same stuff as the sea and land that separate him from his beloved. From this perspective, looking at a landscape is like looking into the inner life of a human being.

For all its apparent pre-scientific naiveté, the theory of “four humours” recognises our essential unity with nature, in a striking contrast to the more modern experience of an isolated self.

Alan Watt writes in “The book: on the taboo of knowing who you are”:

“Most of us have the sensation that “I myself” is a separate center of feeling and action, living inside and bounded by the physical body—a center which “confronts” an “external” world of people and things, making contact through the senses with a universe both alien and strange. Everyday figures of speech reflect this illusion. “I came into this world.” “You must face reality.” “The conquest of nature.”

This feeling of being lonely and very temporary visitors in the universe is in flat contradiction to everything known about man (and all other living organisms) in the sciences. We do not “come into” this world; we come out of it, as leaves from a tree. As the ocean “waves,” the universe “peoples.” Every individual is an expression of the whole realm of nature, a unique action of the total universe.”

But the sciences (be they modern or antiquated) cannot really touch us emotionally — after all, that’s not how they are supposed to work. One can read a hundred books about one’s thoughts and desires being — if not exactly air and fire, but some bundles of electrochemical activities in a highly organised lump of neural cells, which are themselves highly organised lumps of simpler elements — and all this knowledge won’t change the emotional experience of lonely self in the slightest.

Poetry, though, is another matter entirely.

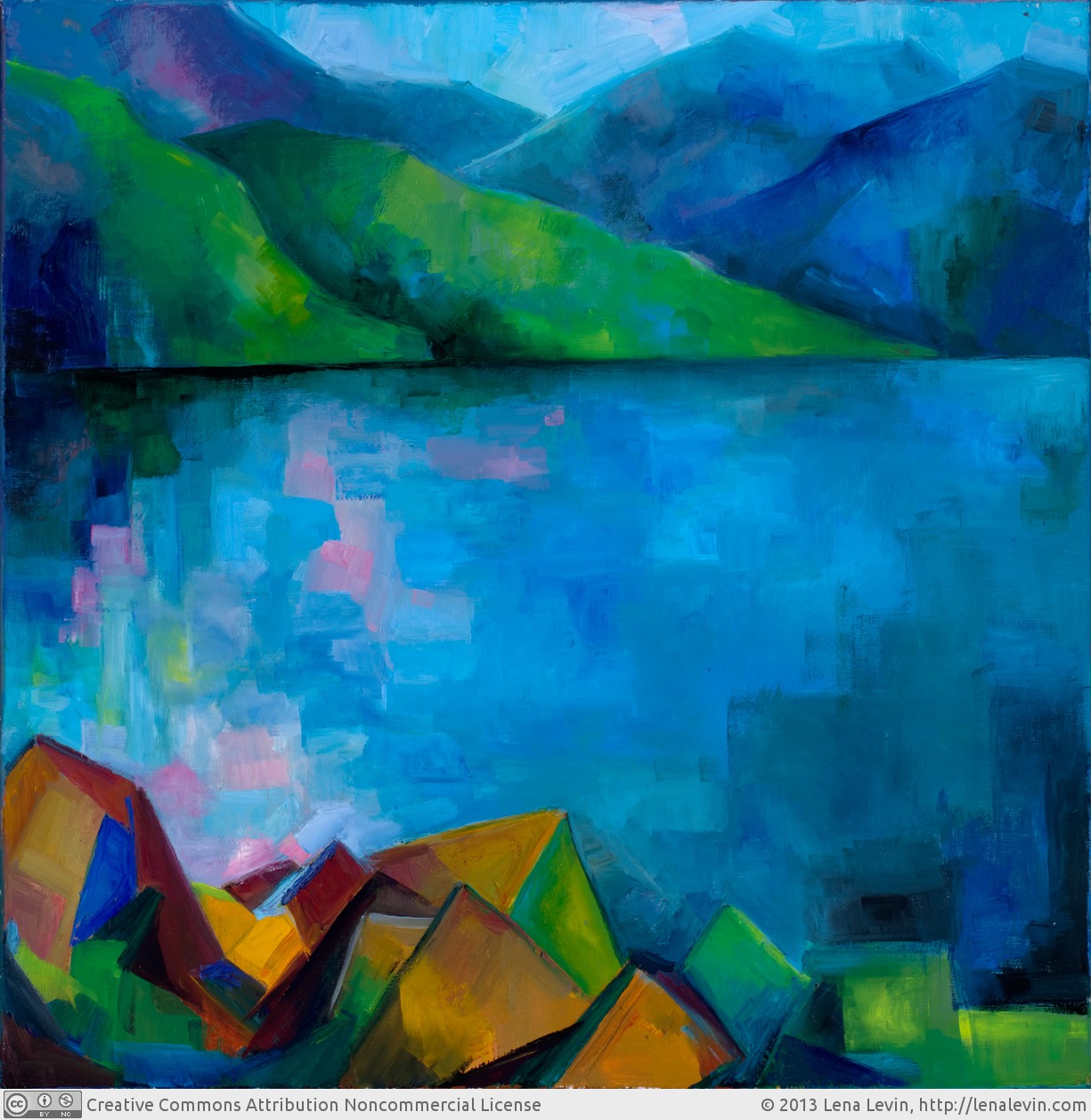

Letting this sonnet sink into myself, living with its change of rhythm from nimble jumps to heavy slowness, with its almost imperceptible transformation of see and land into tears and dullness, I cannot help but feel this unity, perceive it as my own experience. The landscape (or, more precisely, the seascape) that emerged as my painting translation of this sonnet fuses together several of my own impressions associated with the images of distance, space, separation.

[visibility type=”hidden-phone”]

[block_grid type=”two-up”][block_grid_item]

[/block_grid_item][block_grid_item]

[/block_grid_item]

[/block_grid]

[/visibility]

But the sonnet isn’t simply a poetic expression of the “four humours” theory with its inherent unity between man and nature. There is a tension between two world views, two experiences of self: the ancient identity of fundamental elements in all their manifestations (from sea and land to human woes and dullness) versus the modern separation between thoughts and flesh, which echoes the separation between the lovers. A clash between antiquity and modernity.

The process of painting reflected this tension: I felt it as a continual struggle between two opposing impulses: one drove me towards establishing a clear contrast between nimble thought and dull substance of flesh, while the other kept trying to obliterate these contrasts in favour of unity, to dissolve the self-imposed formal boundaries (which seemed increasingly artificial and simplistic). The painting, as it is now, emerged as a blend of partially erased pictorial contrasts — in the blue-green colour harmony, in the horizontally divided composition, in the opposing rhythms in different areas of the painting.

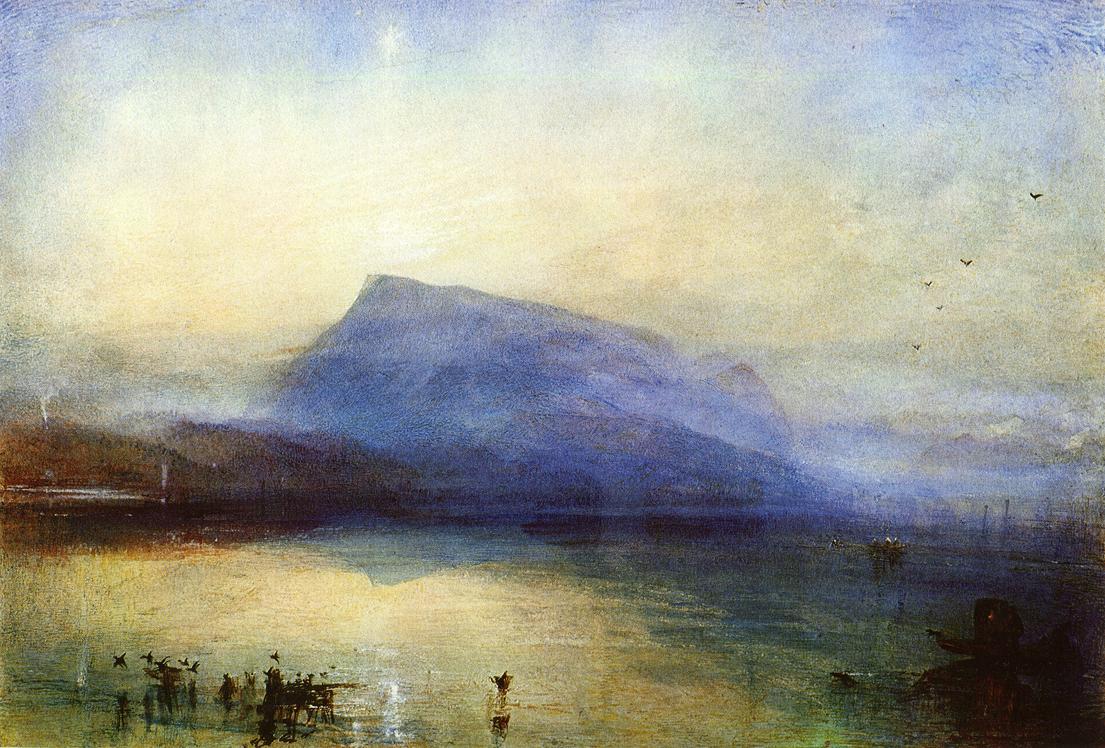

In the end, the painting’s organising contrast, which clarified itself in the process, is between the heavy, cubist-like geometry with its hard, rectilinear edges — and the light, subtle, almost Turner-like build-up of closely related colours. Somehow — I cannot really tell why — this contrast stands, for me, for all the multilayered oppositions of the sonnet at the same time: flesh versus thought, water and earth versus air and fire, isolation versus unity, modernity versus antiquity.

[share title=”If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, please consider sharing it with your friends!” facebook=”true” twitter=”true” google_plus=”true” linkedin=”true” pinterest=”true” reddit=”true” email=”true”]