The temporary exile from my studio didn’t necessarily mean I couldn’t paint: after all, there is all my plein air gear out there in the garage — I could just go out and paint landscapes every day. But I didn’t. It seemed too cumbersome to store oil paintings in this tiny hotel room; and I felt tired and a bit ill, so I decided to just take time to reflect, and to read, and just give myself some breathing space.

And so it came to happen that I didn’t paint for two weeks or so — an unusually long interruption in the painting process.

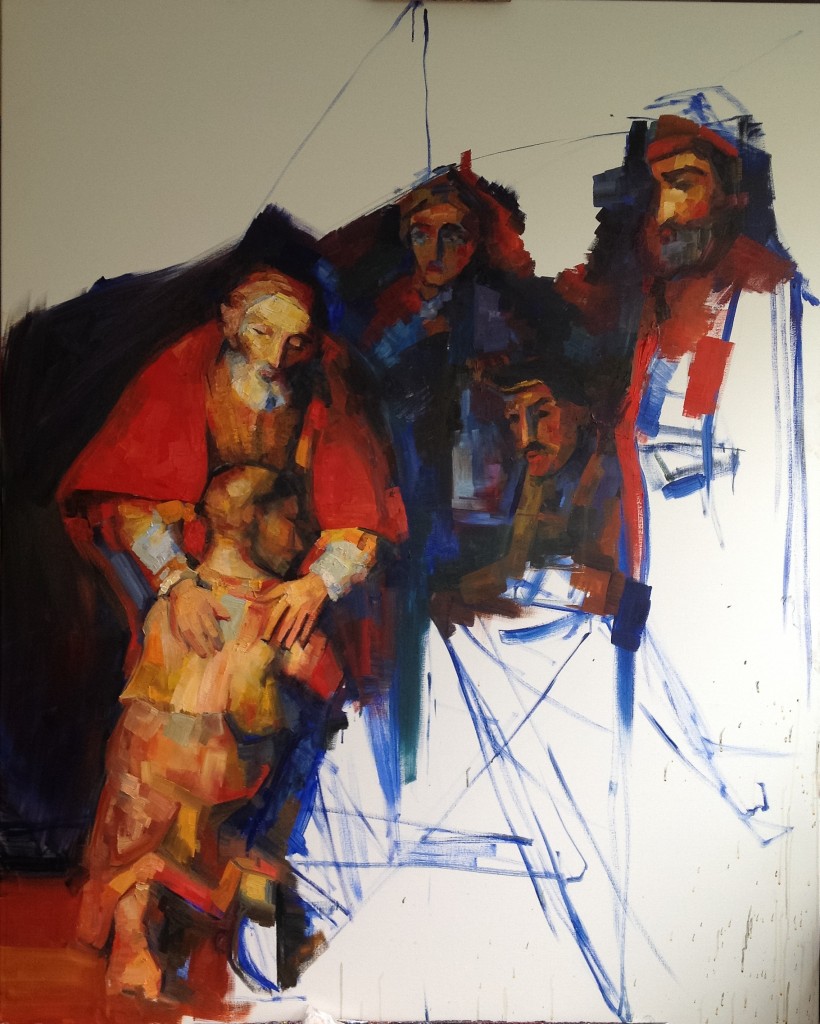

Back in the studio, I decided to start with my huge Rembrandt study. This kind of communion with Rembrandt felt just like the right way to break the painting fast. As it turned out, there was even more to this feeling that I had anticipated: this return to painting felt exactly like the return of the prodigal son in the parable, and in Rembrandt’s painting.

It may seem ridiculous — after all, a fortnight away doesn’t seem to qualify for such a grand interpretation. But the truth, there was a time in my life when I abandoned painting for years — for decades even — prodigally spending whatever gifts and talents I was given in other pursuits. This, I believe, is why even short pauses in my studio work tend to trigger fears and doubts: each of them feels, at some level, like that decades-long time away from myself. I am afraid that I won’t be able to return, that Painting won’t take me back, that the door will be closed forever.

Hence the core experience of my first painting session — sensing that Painting does accept me back, with the same unconditional, raspberry-coloured tenderness as the father accepts his prodigal son in Rembrandt’s painting.

And in the course of this painting session, I suddenly remembered that I did see myself in the parable of the prodigal son back then. A couple of years after I had abandoned painting, a poem came to me — a poem where I promised to return, just like the prodigal son did; or to be more precise, a poem predicting this return. It now seems very strange that I had forgotten that poem, and didn’t even recall it when I started this Rembrandt study a couple of months ago. Could it be that this whole hiatus was actually needed to continue this study, to feel my way into it at a deeper level?

But there is more to it… The thing is, I’ve been painting “full time” for many years now. These two weeks for the renovation project have, objectively speaking, nothing to do with the long years of my “prodigal” youth. So why is it that the fears I seem to have overcome when I came back to painting back in the beginning of this century — why do they re-surface so easily, with a minimal “trigger”? Why am I so terrified of even brief disturbances to my studio “routine”, as though each of them is just waiting to transform into a lifetime of exile from painting?

In an instance of serendipity, or synchronicity (or whatever is the right word for this kind of happenings), I followed someone’s link to Paramahamsa Nithyananda’s book, “Living enlightenment” (at Lifeblissprogams.org), and read my way towards the chapter on fear. His take on fears is somewhat different from what I have encountered so far — because here, fear presents itself not as something to be conquered, not as a sign of weakness, but almost something to be celebrated. He writes:

<…> fear is a part of the nature of life. You can be fearless if you are already in your grave! Then there is no need to be afraid of anything because you have nothing to lose. If you have something to lose, you will have fear. This is the nature of life itself.

His advice, then, is neither to fight the fear you are facing (because this empowers it), nor to distract yourself from the fear (because then it stays with you, just hidden from your conscious attention), but just to “look at it”, live it, accept it. I guess my favourite strategy all these years used to be not to pay attention to fears. It has the obvious advantage of doing what you’ve got to do in spite of any fears, but it keeps the fears well and alive in your inner space, always ready to resurface.

And when I decided to follow his advice and look directly at my fear of “painting not taking me back”, I saw another, deeper and darker fear lurking behind it: the fear of being completely and utterly delusional about my whole relationship with painting; the fear of being delusional about being an artist. It scares the hell out of me — even now, as I write the words, I feel as though I am making this potentiality more “real” than it would have been had it remained in the darkness, outside the realm of conscious “naming”. But this makes my next challenge clear: to live and accept that fear. Paramahamsa Nithyananda writes:

<…> fearlessness doesn’t mean non-existence of fear. It means the fear is there, but you have tremendous energy or courage to live with it and face it. Fearlessness means the energy or the courage to live even with the maximum fear — going beyond that fear and being neither attached not detached from the fear.

The next question to live is, then, whether I happen to have this energy or this courage… We’ll see, I guess.