Our subjective experience of time is one of the most mysterious and paradoxical things I know. Mostly, we seem to just flow with the time, unable or unwilling to step outside and marvel at the strangeness of the whole experience.

Shakespeare’s “horseback” sonnets (fifty and fifty one) give us an opportunity to look at this strangeness “from the outside”, while still experiencing its emotional repercussions vicariously. They share a very well-defined “objective” setting: their speaker is on a road, riding away from his beloved. The scene is so concrete and tangible that it’s easy to think about these sonnets as a missing soliloquy from “Romeo and Juliet”: Romeo on the road to Mantua.

The continuity of this setting forms the background for an amazingly swift and drastic change of the speaker’s subjective experience. Heaviness, sadness, and anger of the fiftieth sonnet transform into lightness, joy, and love in the fifty first. Even the speed of the horse seems to have increased dramatically, but this cannot be the case — what have changed instead is the rider’s experience of time.

Just try to read these sonnets aloud to yourself to feel this change and notice how the rhythm changes, reflecting this increasing speed (or, if you prefer to listen to them, click the first line to hear Edward Bennett reading them):

How heavy do I journey on the way,

When what I seek, my weary travel’s end,

Doth teach that ease and that repose to say,

‘Thus far the miles are measured from thy friend!’

The beast that bears me, tired with my woe,

Plods dully on, to bear that weight in me,

As if by some instinct the wretch did know

His rider loved not speed being made from thee.

The bloody spur cannot provoke him on,

That sometimes anger thrusts into his hide,

Which heavily he answers with a groan,

More sharp to me than spurring to his side;

For that same groan doth put this in my mind,

My grief lies onward, and my joy behind.

Thus can my love excuse the slow offence

Of my dull bearer when from thee I speed:

From where thou art why should I haste me thence?

Till I return, of posting is no need.

O what excuse will my poor beast then find,

When swift extremity can seem but slow?

Then should I spur, though mounted on the wind;

In winged speed no motion shall I know:

Then can no horse with my desire keep pace;

Therefore desire of perfect’st love being made,

Shall neigh — no dull flesh — in his fiery race;

But love, for love, thus shall excuse my jade:

Since from thee going he went wilful slow,

Towards thee I’ll run, and give him leave to go.

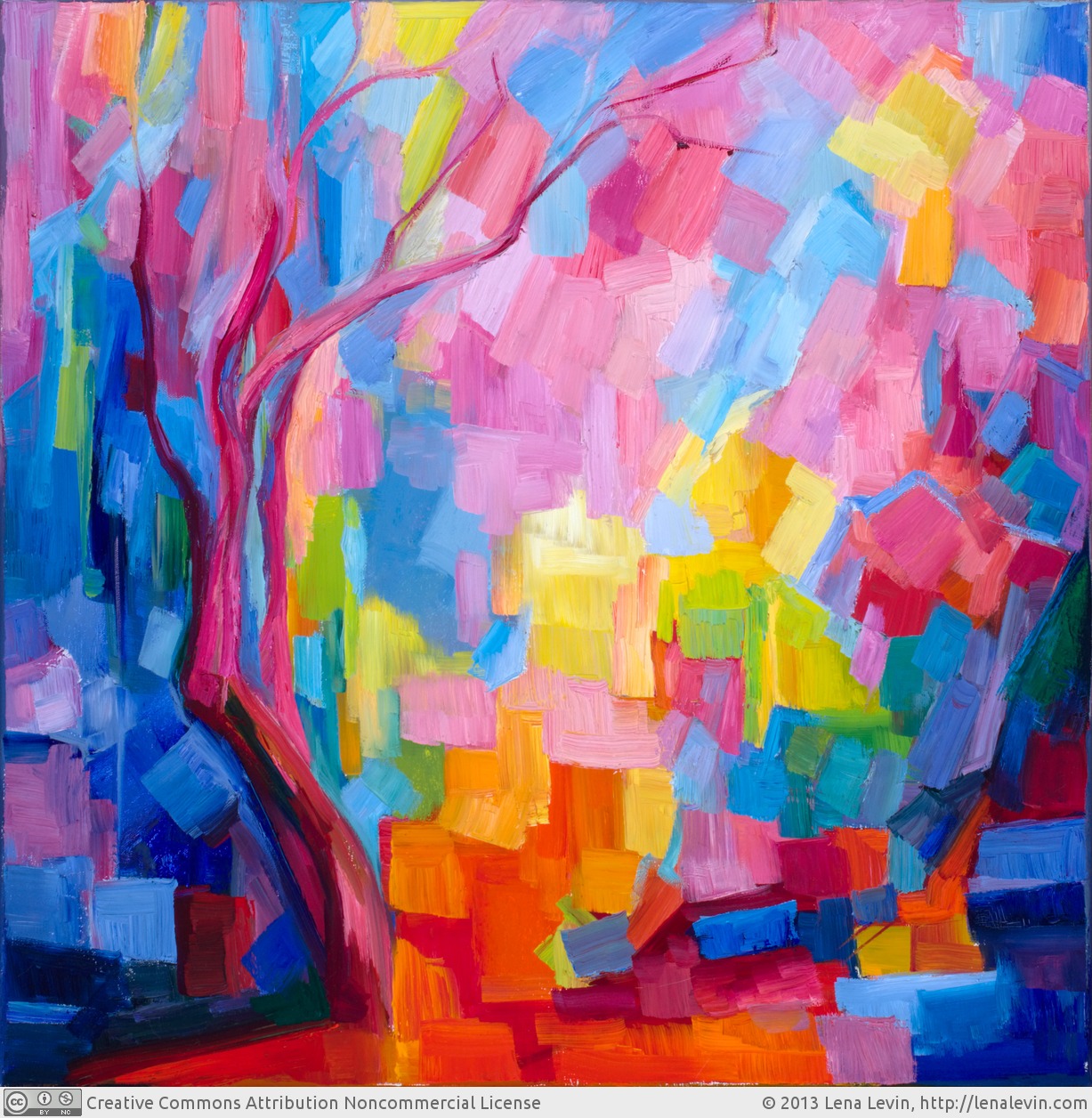

The question was, how to translate this transformation into the language of painting?

The answer I found is in the next question: how the rider sees what’s in front of him before and after the transformation? Since its the mind that constructs visible “reality” from the data supplied by the eyes, the view must change dramatically. This is what these two paintings show: one landscape as seen from inside two different states of mind.

If you don’t think such a change is possible, it’s just because such extreme changes in the inner state tend to detract our attention from visual experiences.

But how did this happen?

A levelheaded, reasonable person might probably answer that the speaker sees things “as they really are”, “objectively” in the first sonnet — but then moves to a dreamy (if not downright hallucinatory) state in the second. I must admit, my paintings might seem to suggest something of this interpretation: the first one certainly looks more “representational” than the second — but wouldn’t the swift extremity of motion blur the landscape?

Anyway, I believe this reasonable character I imagined in the previous paragraph would miss the whole point: the mental shift that accomplished this transformation is not from “objective reality” to a hallucination, and not from the present to the future — but from one future to another, just a bit more distant one. If someone looked at the whole scene really, really “objectively”, from outside the speaker’s mind, then the momentary present state of affairs would be exactly the same on the journey back — the same road, the same horse, the same aloneness of the rider (well, the horse would be looking in the opposite direction, but this certainly isn’t enough to explain the sudden change of mood).

This means it is not the present that is reflected in the rider’s gloomy mood in the first sonnet, it’s the future — the future of being away from the beloved. This future shapes the rider’s present into the sensations of weight in me, sadness and irrational anger towards the poor beast (who, after all, just follows his unexpressed wish to slow down even more). That’s why this swift shift to another future is enough to change subjective experience of the present so completely. And after all, the moment-to-moment subjective experience is all we have — and thus the future appears to define the present (instead of being determined by it, as we ordinarily think about it).

Why is it that the future has so much power over the present?

Take love, for example: the illusion of “happy ever-after” is so seductive that the genuineness of present love is often equated with its indefinite extension into the future. If we followed this idea to its logical conclusion, it would turn out that one cannot know for sure if the love they feel now is “true” until they are dead. Doesn’t this sound absurd? Thankfully, love tends to bring one into the present moment so forcefully and irresistibly that the subjective experience of time almost dissolves into thin air, as though the time didn’t exist at all. Otherwise, the uncertainty of future would lead us to hopelessly loveless lives and cancel any possibility of “happy ever-after” altogether.

What if, like I suggested in the beginning of this post, we read these sonnets as a “missing scene” from “Romeo and Juliet”? Here are the words that would precede this scene (the link will take you to the whole farewell scene on the “Open source Shakespeare” website):

Juliet: O think’st thou we shall ever meet again?

Romeo: I doubt it not; and all these woes shall serve

For sweet discourses in our time to come.

This the exact same motion of the mind towards another future that we see in the sonnets (this parallel is what made me imagine the speaker of the sonnets as Romeo in the first place). But if the rider of the sonnets is Romeo, then we know that this better future never happened; Romeo’s return to Verona was in fact more tragic than the journey to Mantua. But what of that? When this new present came, it could in no way change the quality of this moment. Romeo just creates for himself a present moment of love-filled joy out of thin air (just like Juliet creates an earlier moment of togetherness by believing that a lark is a nightingale, and that it is not yet near day in the farewell scene). And in the timeframe of their short lives, every moment of joy is worth a year at least.

The Romeo and Juliet interpretation of the sonnets is, of course, totally speculative. It’s just a way to illustrate the idea that the future need not exist to affect the present. These three scenes — Romeo and Juliet’s farewell, his journey away, and his journey back — are nested within one another like Matryoshka dolls: as the farewell contains the journey away as its defining moment, so the journey away contains the journey back. This nesting seems to me to be a fitting metaphor for all the futures that shape our present moments: they are contained within the present, and that’s where their power over it comes from.

It’s quite likely that what I will say in conclusion is the most obvious thing in the world for you — or, on the contrary, it might sound most counterintuitive and bizarre. As for me, I tend to vacillate between these points of view, yet these sonnets made me experience the visceral truth of this: At any present moment, the future doesn’t exist except within this moment (and of course, only insofar as it is present within someone’s mind).

The good news, of course, is that one can choose a “future” that shapes their personal present with sheer power of imagination — and see the world transform, (more or less) as it does in these two paintings.

[share title=”If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, please consider sharing it with your friends!” facebook=”true” twitter=”true” google_plus=”true” linkedin=”true” pinterest=”true” reddit=”true” email=”true”]