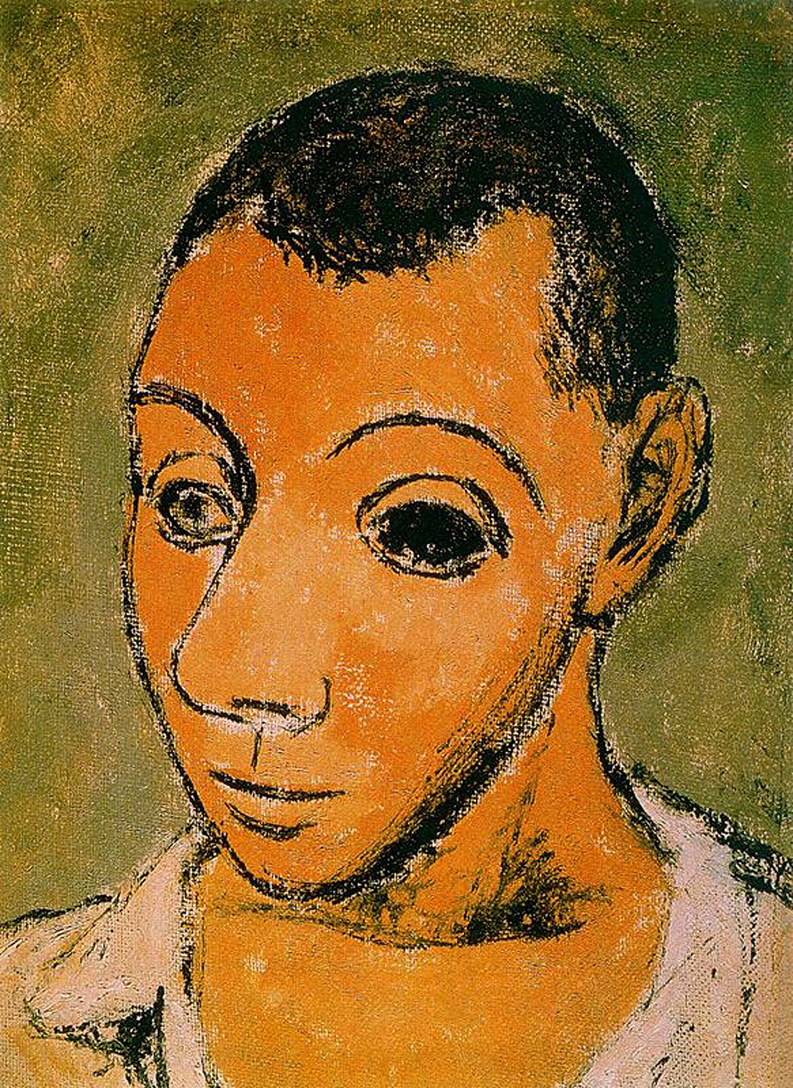

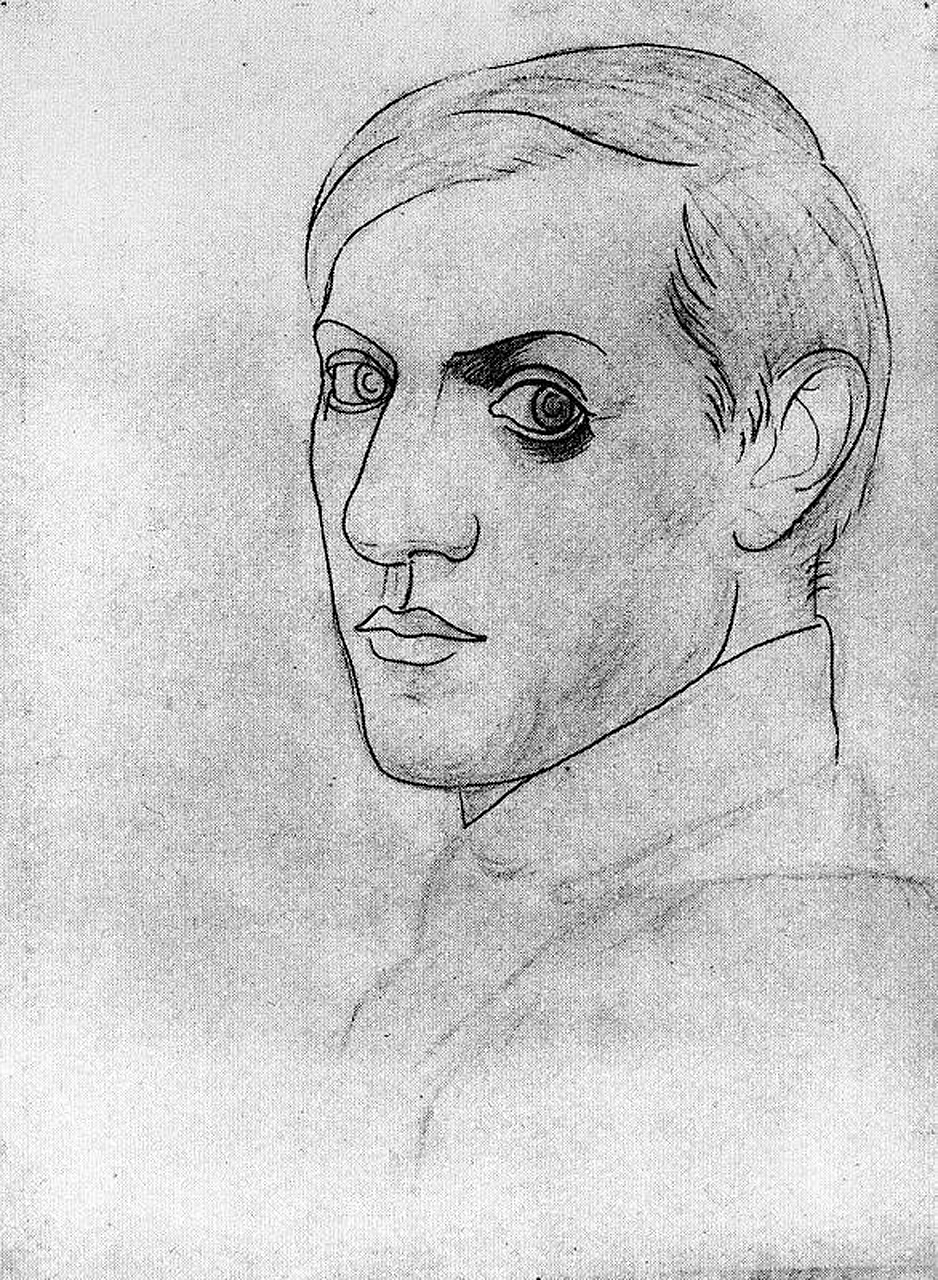

Picasso said once that it took him four years to paint like Rafael, and a lifetime to paint like a child. I believe he knew — consciously or not — that knowledge, and even mastery, not only expands our abilities, but also limits them.

The limiting power of knowledge is known as Einstellung — the German word for “installation”, or “setting”. The initial experiments which gave rise to this concept involved two groups of children. Both groups were (eventually) given the same math problem, but one faired much better at solving it than the other.

The difference? The children in the first group were just given this one problem to solve, without any preparation. The other children were first presented with five similar-looking problems, all of which could be solved with the same algorithm. But this algorithm didn’t work for the sixth problem — some modifications were needed, and the children failed to find them. The five problems they had just solved effectively blocked their brains from finding the solution, which — in itself — wasn’t hard to find at all. In other words, the first idea of a solution which pops into one’s head “installs” itself in the brain as a kind of brick wall hindering the view.

If the problem were limited to students — to those who are just learning the domain — it wouldn’t be too hard to deal with. All the teacher has to do is alternate problems and challenges, so that no single method of solution can install itself in the student’s head as the only one.

But Einstellung can also happen to experts and masters of their domains. A lot in the process of gaining expertise and mastery has to do with expanding one’s repertoire of familiar patterns and corresponding “automatic” reactions, that is, solutions we use unconsciously. We all know this from learning how to drive — in effect, it’s the process of training our unconscious to deal with all the movements routinely required to get the car moving, and with regularly arising traffic situations. So, for example, when every car in front of you is slowing down, we don’t take time to think through appropriate actions — we do it swiftly and automatically. More or less the same process of learning happens in all human endeavours.

In principle, these automatic, unconscious responses to familiar situations and challenges free our minds to seek creative solutions to non-trivial, novel problems. That’s what mastery and expertise are supposed to be about.

But, in a more recent experiment, master chess players were “blocked” from seeing the best solution to a chess problem, just because it matched a familiar pattern with a well-known solution (which worked, but wasn’t the best one in this particular case). Even if they knew that theirs wasn’t the optimal solution, their view was still hindered by this first idea, which popped into their brain automatically and “installed” itself there. This is how Einstellung works.

What about artists?

Learning in art is essentially the same as in any other domain: it necessarily involves training the unconscious to master a repertoire of ways to make effective compositions, a variety of colour effects, lines and marks with different qualities, etc. That’s the only way to be able to focus on genuinely creative aspects of work, without thinking too much about all the technicalities. But it can have the same “Einstellung” effect: it can block the artist’s ability to see a novel pathway.

So when Picasso talked about learning how to paint like a child, that’s what he might have meant: a quest to gain freedom from the limiting power of his own mastery.

I believe the problem of Einstellung might be even more acute for artists than for scientists and chess players, because modern artists are encouraged, in one way or another, to find “their own style” and then stick to it. Having one’s own recognisable style is equated, in effect, to having found one’s own unique “voice” in art.

But how would one distinguish between this unique voice and the phenomenon of Einstellung, that is, losing the ability to see novel solutions just because your familiar ones have become too well ingrained in your neural pathways? “Your own style” may well turn into this brick wall, effectively blocking the flow of your art.

The question is, then, can we learn to “shake off” the Einstellung? Or, at least, do our best to curb its limiting power?

Picasso’s way was, obviously, to change his style (and his palette) dramatically all the time. I’ve seen other painters use less radical ideas, like removing a favourite colour from their palette to block familiar ways of achieving colour effects, or temporarily switching to another medium, or a new kind of subject matter. For an abstract artist, it might help to try and paint a (recognisable) portrait; for a plein air painter, to try and make something non-representational.

To some extent, it might just help to be aware of the danger. Now that I am, I will certainly be looking for new ways to shake off these installations my brain is building… What about you?