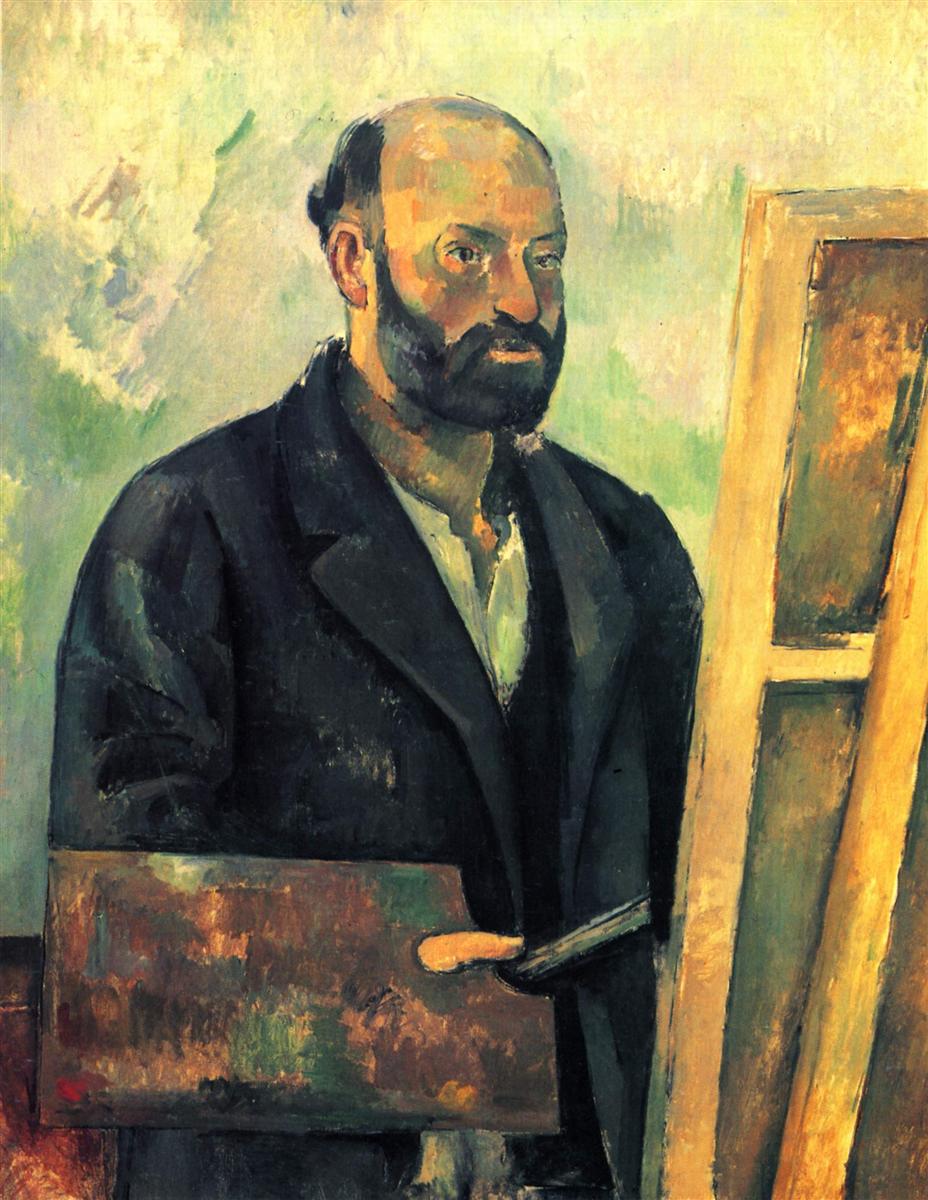

For several weeks in autumn 1907, Rainer Maria Rilke was visiting Cézanne’s memorial retrospective in Paris nearly every day, and spent hours in front of his paintings. This encounter has transformed him, as a man and as a poet, “[b]ut, — he wrote to his wife —

“it takes a long, long time. When I remember the puzzlement and insecurity of one’s first confrontation with his work, along with his name, which was just as new. And then for a long time nothing, and suddenly one has the right eyes …” (from Rainer Maria Rilke. “Letters on Cézanne.”).

But that’s not how paintings are supposed to work, is it? We tend to expect a painting to “resonate” with us immediately, spontaneously. One look at a painting — and the viewer experiences a deep, visceral connection, and only then they would spend more time with it. If the connection doesn’t happen, they just go on to another one. It’s either a love at first sight, or no love at all.

I came across this idea even in some textbooks for artists: if a painting doesn’t evoke an immediate emotional reaction, it failed. And all too often, I behaved accordingly as a viewer.

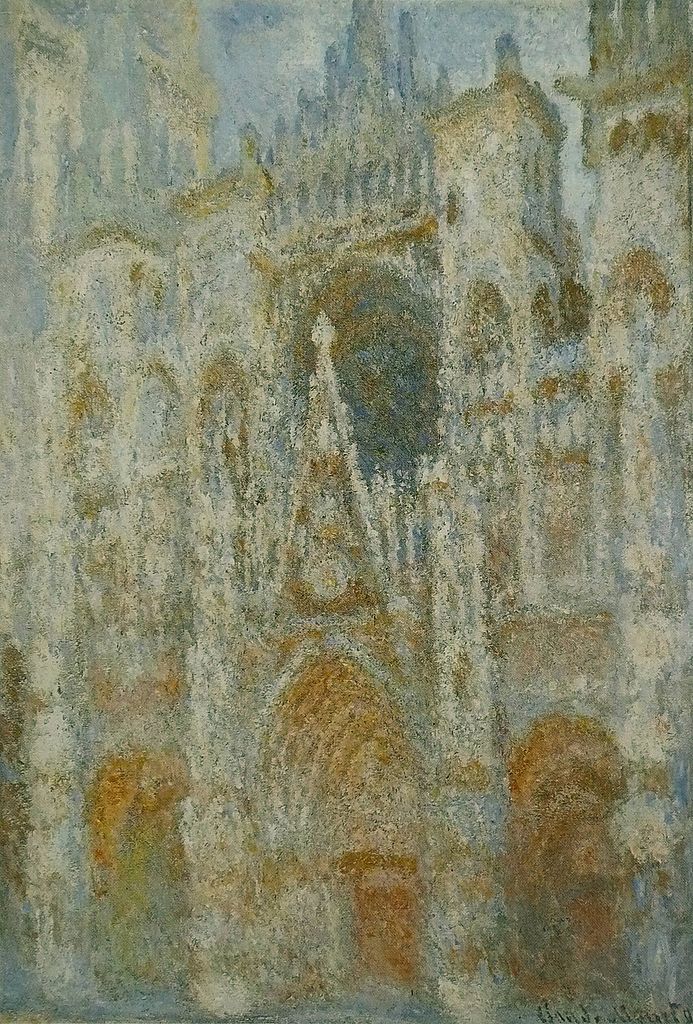

For example, nothing in me “resonated” spontaneously with Claude Monet’s work, and I felt something akin to Rilke’s initial puzzlement and dismay in front of his Rouen cathedral series. I knew about the quality and importance of his contribution to art, but, to me, these paintings looked and felt too formless, their composition too scattered to be meaningful — and I turned away from them, without giving them a chance to work their way into my inner world. After all, there are so many great paintings… it would seem to make sense to spend your limited time in a museum with those that do resonate with you, wouldn’t it?

Except you might miss a transformative experience like Rilke’s — as I now believe I had by passing by Monet’s work many years ago.

This is what I’ve come to understand in the meantime: an immediate sensation of “resonance” between a painting and a viewer, this visceral emotional reaction, must mean that some neural loops in the viewer’s brain which connect something in this particular visual stimulus with their deep-seated emotions, are already there, just waiting to be stirred up. The experience has already been experienced, and the painting makes us re-live it.

Sometimes one can even pinpoint this underlying personal experience. In his book on “Writing for art”, Stephen Cheeke illustrates this with Derek Mahon’s poem about Pieter de Hooch’s painting “Courtyards in Deft”, which ends with these lines (emphasis mine):

I lived there as a boy and know the coal

Glittering in its shed, late-afternoon

Lambency informing the deal table

The ceiling cradled in a radiant spoon.

I must be lying low in a room there,

A strange child with a taste for verse,

While my hard-nosed companions dream of fire

And sword upon perched veldt and fields of rain-swept gorse.

The spontaneous resonance happens when the painting taps into this kind of pre-existing connections between raw emotions and visual impressions. It can strengthen and consolidate the connections, clarify and validate the emotions — but it doesn’t create them, doesn’t really expand the range of our experiences.

The expansion of experience can happen only if you stay with a painting that does not quite resonate at first for a long, long time, like Rilke stayed with Cézanne’s. Then, and only then, can there be a transformation.

All those years ago, I was almost completely disconnected from the experience offered by Claude Monet: the experience of fluid nature of visible reality, the moment-to-moment joy of change, which doesn’t quite give anything enough time to form into a stable, solid shape. It took me decades to find this experience, and to understand how much I have been missing all this time.

I wish I had accepted his help back then, surrendered to his vision — it might have taken a long time to get “the right eyes”, but not nearly as long as it had without his help.

So here is another wish, which might still come true – it’s up to you: maybe one day this story will make you pause in front of a painting that rather puzzles than resonates spontaneously, and give it a chance to work its miracle.