Every once in a while, a genuine breakthrough in science remains unnoticed (or almost unnoticed) and unabsorbed in the relevant domain of knowledge for a long time. The history of science knows many such episodes — but, of course, only those that were “found” and appreciated later on, when the domain was ready, or the intellectual climate has changed. There might have been more — either still waiting to be found, or forgotten forever, or otherwise rediscovered afresh by someone else.

I’ve come to believe Julian Jaynes’s “The origin of consciousness in the breakdown of the bicameral mind” (1976) may be such a breakthrough — if not exactly unnoticed, but certainly underappreciated and unabsorbed by the domains of knowledge which his theory might potentially change. There are many of them — from psychiatry to archeology; the book is refreshingly cross-disciplinary in our age of increasingly stifling specialisation. There might not be a single scholar active in the world today who would be competent enough to evaluate the theory in all its details. As for me, I can only speak for linguistics — the only domain I used to work in — and I truly wish I knew about this book when I did; in fact, I wish it were (formally or informally) part of required reading for all linguists.

Not because Jaynes was necessarily right in all details and nuances of his theory (he probably wasn’t), but because the book questions some very fundamental, core assumptions of the domain — and when they are challenged, it turns out that they aren’t really justified by much more than “common beliefs” and overall intellectual climate of the age. Personally, one of the most life-consuming projects of my years in linguistics both originated and, ultimately, failed, because of my own unquestioned belief in these received assumptions (this research project is way too technical to discuss in the context of this site — and, as I said, it was a failure anyway — but, come to think of it, this work had probably prepared my mind for Jaynes’s book. It may also be, of course, that this is just how my consciousness prefers to build my personal narrative, my own story of my life — just because it would be too hard to accept all those years as total waste).

Luckily for us all, Jaynes was also an excellent writer, and his book is written as though for an intellectually curious layman (rather than just for peers, as scholarly books usually are). Given the cross-disciplinary scope of the book, he probably had no other choice: a peer in one domain is inevitably a layman in another. I may be better versed in general linguistics than he was, but I am certainly nothing but a curious layman in all other domains he touches upon; but even in linguistics, although I do find some details of the theory doubtful (and certainly often speculative), yet it is still an enlightening, even eye-opening read overall.

More importantly still, it was a mind-opener on a more personal level. It has changed the way I see other people, and the world, and my own place in it. In particular, it changed — for me — the historical and intellectual context of this project, Sonnets in Colour, so I will certainly write about it more here in the future. But the book should certainly be read in its mind-boggling entirety — it is really a brilliant book: I am not at all surprised that it is still in print, after nearly forty years since it was first published.

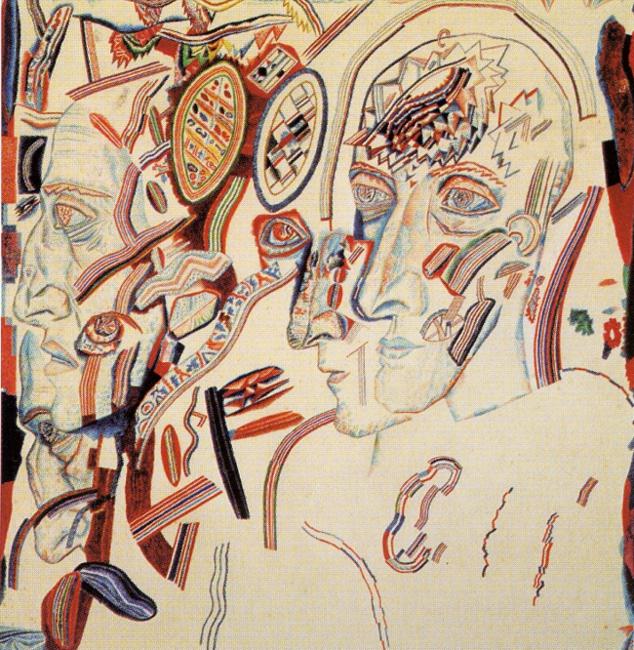

One of the key points of Jaynes’s theory is that consciousness, the subjective human mind as we experience it, could emerge only at a certain, and relatively recent, stage of language evolution. To put it even more strongly, consciousness is generated by language, and lots of things must have happened in the evolution of language from its humble beginnings as rudimentary communication system before such a thing as modern consciousness could become possible.

But what is consciousness? It is simultaneously most self-evident and most elusive thing in the world. Most self-evident because it is our immediate experience of the world (as we know it, or, more precisely — as we know that we know it). Most elusive because we tend to understand things by way of comparing them with something more familiar, more evident, more directly accessible to our outward-directed senses — in short, by finding an appropriate metaphor from the “real world”. But, as Jaynes writes:

“If understanding a thing is arriving at a familiarizing metaphor for it, then we can see that there always will be a difficulty in understanding consciousness. For it should be immediately apparent that there is not and cannot be anything in our immediate experience that is like immediate experience itself. There is therefore a sense in which we shall never be able to understand consciousness in the same way that we can understand things that we are conscious of.”

Incidentally, as far as I could gather, much of the controversy around Jaynes’s theory when it was first published was generated by huge differences in how the very word, “consciousness”, was understood (and a range of derivative words, corresponding to — supposedly — different types of consciousnesses, have been introduced since then, which didn’t make things much clearer). It was not, I believe, because of Jaynes’s failure to define what he is talking about, nor of his readers’ failure to understand his definition. It might just be in the nature of consciousness to hide from itself, to resist observation and analysis: turning consciousness upon itself makes one quite giddy and all but makes the concept itself dissolve into thin air.

And it’s also in consciousness’s nature to present itself as a much deeper, larger, essential part of our mental life than it really is. However it is defined, it is clear that a lot happens in our minds without us being conscious of it at all. Jaynes himself uses the metaphor of flashlight:

“Consciousness is a much smaller part of our mental life than we are conscious of, because we cannot be conscious of what we are not conscious of. How simple that is to say; how difficult to appreciate! It is like asking a flashlight in a dark room to search around for something that does not have any light shining upon it. The flashlight, since there is light in whatever direction it turns, would have to conclude that there is light everywhere. And so consciousness can seem to pervade all mentality when actually it does not.”

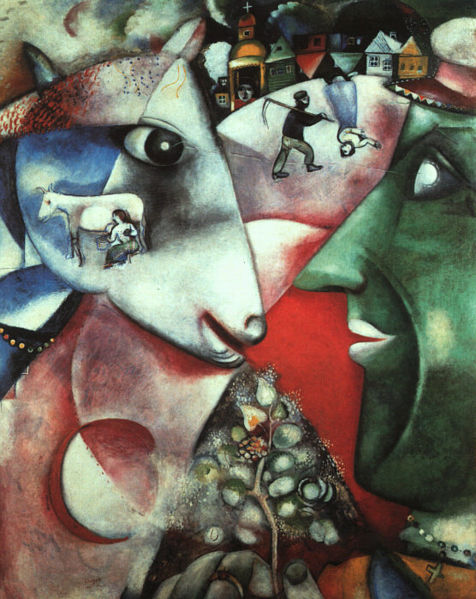

I’ve used the word “metaphor” twice in this post so far, but there are hundreds of metaphors in it already. Just for instance, I called consciousness a thing a couple of paragraphs above, just because it easier to talk about things; that’s how nouns of our languages work, even though we routinely use them to point to things which aren’t things at all (like consciousness, for example). And just now, I said that nouns “work”, implicitly drawing in the metaphor of language as some sort of machine. That’s the way we talk, mostly without noticing it and, as a matter of habit, using metaphors that are already deeply embedded in our languages. But the way we talk is, more or less, the way we think, at least consciously — and this understanding is at the core of Jaynes’s argument.

And there is an important historical dimension to it, because metaphors that are now so deeply embedded in languages that we don’t even recognise them as such were once quite fresh and new — like, for example, Jaynes’s metaphor of consciousness as flashlight above. And before they were new, they didn’t exist at all — it took a long, long time to extend language’s capacity to its current familiar state, and for all this time consciousness as we know it couldn’t exist.

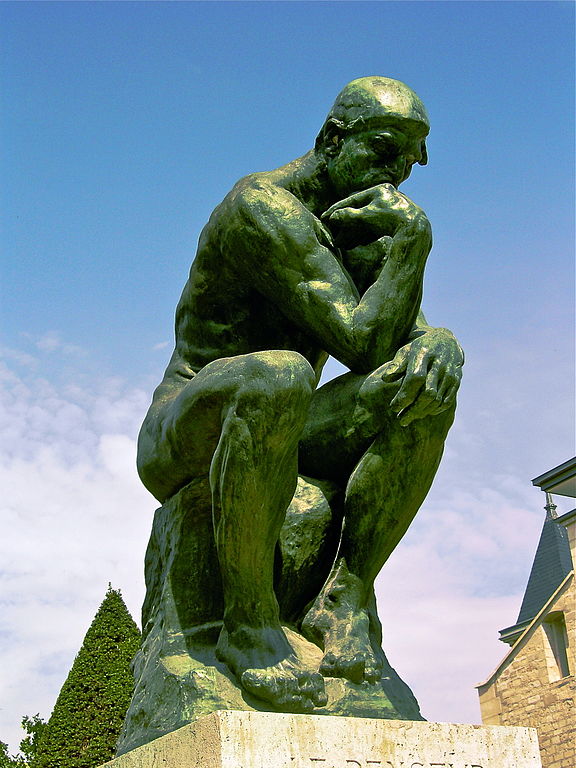

I will return to the topic of metaphors and Jaynes’s idea of their consciousness-generating potential next week. For now, let me introduce one essential example of metaphor: the mind-space, that inner space into which one can go to think, to ask oneself questions, to recall one’s memories or to imagine the future, where one can see solutions and grasp complex ideas — in other words, the space where consciousness “takes place”. Jaynes writes:

“<…>when we introspect, we seem to look inward on an inner space somewhere behind our eyes. But what on earth do we mean by ‘look’? We even close our eyes sometimes to introspect even more clearly. Upon what? Its spatial character seems unquestionable. Moreover we seem to move or at least ‘look’ in different directions. And if we press ourselves too strongly to further characterise this space (apart from its imagined contents), we feel a vague irritation, as if there were something that did not want to be known, some quality which to question was somehow ungrateful, like rudeness in a friendly place.”

Not only do we “have” this space within our heads, but we also assume it in others, even though

“we know perfectly well that there is no such space in anyone’s head at all! There is nothing inside my head or yours except physiological tissue of one sort or another. <…> It means that we are continually inventing these spaces in our own and other people’s heads, knowing perfectly well that they don’t exist anatomically; and the location of these ‘spaces’ is indeed quite arbitrary. The Aristotelian writings, for example, located consciousness or the abode of thought in and just above the heart, believing the brain to be a mere cooling organ since it was insensitive to touch or injury.”

Wherever it is located, this illusionary inner space seems absolutely essential to the very existence of conscious thought, and it is implied in a whole range of everyday words and expressions. But where does it come from, and when did it originate?

I’ll be back with Jaynes’s answer to this question next week — please stay tuned!

[share title=”If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, please consider sharing it with your friends!” facebook=”true” twitter=”true” google_plus=”true” linkedin=”true” pinterest=”true” reddit=”true” email=”true”]