Sonnet 1. Thyself thy foe

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty's rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory:

But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed'st thy light's flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel.

Thou that art now the world's fresh ornament

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content

And, tender churl, mak'st waste in niggarding.

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world's due, by the grave and thee.

Conversation (March 29, 2020). Introductory remarks

(Scroll to read the write-up of main points and what has been emerging in the following conversation)

Main points and emerging themes

In the more traditional reading of the sonnets sequence, the first “act” of this drama, the first chapter of the whole story, comprises sonnets 1-17, which are all about the speaker of the sonnet — an older man — trying to convince a young man to marry and have children. (And, then, starting with sonnet 18, the whole theme of procreation is forgotten, for the sake of romantic love).

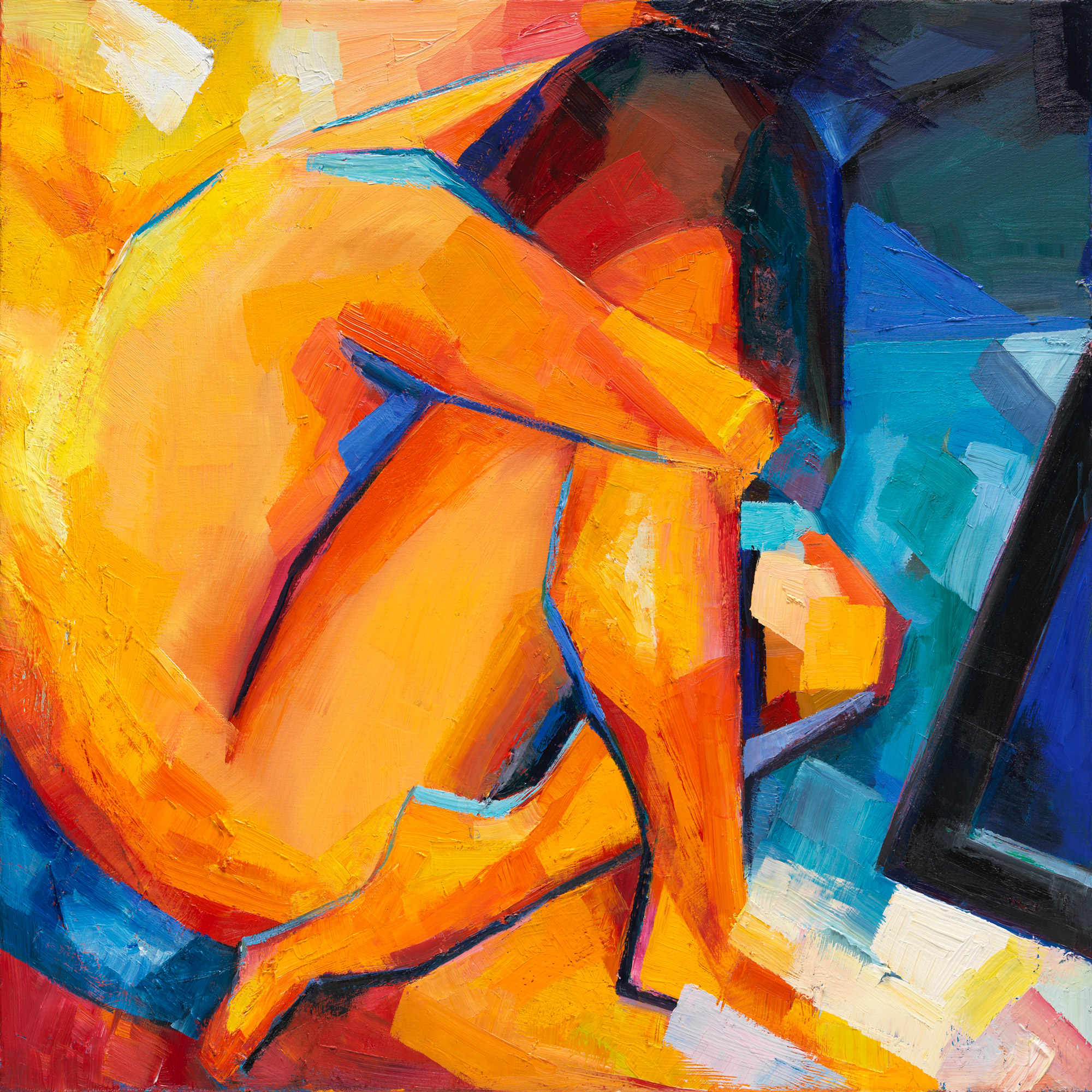

While the theme of procreation is — obviously — present in the sonnets, Shakespeare’s manifold analogies and metaphors expand it into a broader exploration of the paradoxical nature of human “self” in its relationship to the whole, to the world. In its pursuit of happiness and comfort, the wilful egoic self closes itself off from the flow of life, and — in doing so, incurs the curse of mortality. It is only in giving oneself to the whole that one can transcend death and become immortal.

In the structure that emerged in the process of painting the sonnets — or rather, of sonnets reinventing themselves as paintings — the opening sequence consists of two nine-sonnet “collages”, or chapters: “Paradox of Self” (1-9) and “Paradox of Death” (10-18). Thus, the sequence is bookended by two sonnets:

- Sonnet 1, which introduces main themes, metaphors, and images of the whole sequence, and especially the theme of separate Self as its own foe, and

- Sonnet 18, probably the most famous love poem in the English literature (“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day”).

Quite remarkably — for poems written four centuries ago — Shakespeare never thinks of immortality as any kind of eternal after-life. The only attainable immortality is here, on this earth — and its “secret” lies in participation in the flow of life through procreation — but also in immortalising power of Art (the closest one can get to eternity in Shakespeare’s universe).

But Art itself cannot participate in the flow of life without its spectators and its listeners — it cannot live without us, nor can it help us without our participation. This is the context of our conversations.

In our conversation, we began to explore how the sonnet resonates with our own lives:

- How is it that we might be making a famine where abundance lies by being self-substantial? Isn't it a paradox? Isn't it a good thing: to be self-reliant and independent? But in thinking ourselves so, aren't we also closing ourselves from life, filled as it is with inter-dependencies and interconnectivity?

- What are we hoarding? How are we not sharing the gifts we are given with the world? And why? And how can we share them, especially if the response is not immediately obvious?

- One insight that seemed particularly relevant is that what makes us "contract" to our selves, to refrain from sharing and participation in life, is the voice of scepticism: does it all really matter? Can beauty save the world? It is often easier to believe that there is no hope, because then, what can we do? But if there is hope, then it is up to us: if the future of the world depends on us, this requires courage (just as it takes courage to bring a new human into the world).

(The ground rule of these conversations is that only introductions are recorded. To participate in the conversation itself, you are invited to participate, to be there — with us, and with the sonnet!).

Sonnet 2: To be new made when thou art old

When forty winters shall besiege thy brow,

And dig deep trenches in thy beauty's field,

Thy youth's proud livery, so gazed on now,

Will be a tatter'd weed, of small worth held:

Then being ask'd where all thy beauty lies,

Where all the treasure of thy lusty days,

To say, within thine own deep-sunken eyes,

Were an all-eating shame and thriftless praise.

How much more praise deserved thy beauty's use,

If thou couldst answer 'This fair child of mine

Shall sum my count and make my old excuse,'

Proving his beauty by succession thine!

This were to be new made when thou art old,

And see thy blood warm when thou feel'st it cold.

Conversation (April 5, 2020): Introductory remarks

How this sonnet connected itself with van Gogh's paintings

(scroll to read the write up of the main points)

Our “normal” relationship with language is to just “get to the point”, to what is actually being said (or so we think) — to collapse all metaphors, all imagery into a simple proposition, simple, straightforward argument. If we approach this sonnet like this, this is, more or less, the interpretation we get:

⁃ “When you are forty years old, all wrinkled and with deep-sunken eyes, nobody will look at you anymore, let alone adore you like now. And if they look at you at all, they will ask you, where is all thy beauty. But wouldn’t it be nice if you could show off your (as yet not born) son, and say that this is actually your beauty…”

But this is not how the sonnet longs to be read. Instead, it invites us to live and experience its metaphors, to swim in the semantic and acoustic waves and currents these words create — to allow these words to mean what they mean, as a melody played on the musical instrument of language living within us?

And so, in the first stanza — it’s not just “forty years of age”, its forty winters, surrounding and laying siege on the fortress that is your Self, like enemy armies… their war machines digging deep trenches in the field of beauty surrounding this fortress… And all is lost — and the cherished flowers are turned to tattered weed… And one wonders, momentarily: were these war machines or our agricultural machines.

This stanza — when we read it like this — creates the sense of identity between thou (= the reader of the sonnet), and the earth itself — her fields, her trees, her flowers. And it is from the space of this identity that van Gogh’s paintings to enter into my personal connection with this sonnet — and participate in the emergence of my painting translation — an old, dying, naked tree in the foreground, and a another, in the distance, whose blooming branches share their colour with the sky, and dissolve into it.

(In the video, this inner connection with van Gogh is shown line-by-line, moment-to-moment.)

In contrast to the first sonnet, this one focuses not on the idea of self “as a whole”, but on one particular quality, or ideal, with which a “self”, a separate self, may identify itself and their worth. In this case, it is beauty (an attribute of youth) — and it puts this quality in the context of fading and renewal — old and new.

The second and third stanzas allow us to experience two alternative futures, a fork in the unfoldment of life: one, in which this quality is localised, constrained, limited to the self — and another —where beauty it not localised in one being, but spills over to another, expands — and then, the past and the future meet in the present… the old and the new are not in contradiction to one another anymore.

To be new made when thou art old — if we come to these words after this journey through the poem, having lived and experienced the flow its imagery and its metaphors, and this evolutionary fork, what do these words now mean? What does it mean for you: to be new made when thou art old?

The potential of this question is much broader, much more expansive than the renewal we experience through our children and grandchildren..

What comes to my mind, then, is the dream of butterfly — the miraculous transfiguration of a caterpillar, a completely new creature emerging from the old. It offers one interpretation, one way to understand what’s going on with us now, at this point of our evolution: humanity undergoing a radical mutation, a new humanity, a butterfly-humanity, being birthed through us, in us, as us…

Sonnet 3. Thy golden time

Look in thy glass, and tell the face thou viewest

Now is the time that face should form another;

Whose fresh repair if now thou not renewest,

Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother,

For where is she so fair whose unear'd womb

Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

Or who is he so fond will be the tomb

Of his self-love, to stop posterity?

Thou art thy mother's glass, and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime:

So thou through windows of thine age shall see

Despite of wrinkles this thy golden time.

But if thou live remember'd not to be

Die single, and thine image dies with thee.

Conversation (April 19, 2020): Introductory remarks

Yin and Yang, Life and Death

(scroll down to read the main points)

In most other Shakespearean sonnets, there is at least one “key word”, which runs through the body of the sonnet and re-appears in the couplet (that is, the last two lines). And often, this word is really the key that “unlocks” the sonnet.

But here, in Sonnet 3, there are no lexical ties between the sonnet and its couplet, but this very absence might be the key to it its meaning and to its inner music.The transition to the couplet is abrupt, not only lexically (= no shared words), but also rhythmically — as though a smooth flow of life is interrupted, suddenly and violently.

The transition as abrupt as death itself is so often perceived to be.

As though the whole sonnet is this one single beat: live/die.

But if we look closer at the body of the sonnet, this fundamental semantic binary occurs again and again, at different scales as it were, present in every quatrain, almost in every line (and perhaps most conspicuously, in the womb/tomb rhyme in the second stanza).

Just like in life:

We live, and then we die. But this primordial binary is not just the general “outline” of a human life, flowing from moment to moment until it ends abruptly in death. It is also the essence of its every moment, every heartbeat: live/die; birth/death; growth/decay.

In this incredibly complex ecosystem, a human being, something is always dying, and something else comes alive — and at some level, this is also a choice being made in every moment anew: live/die, expand/contract, womb/tomb. (In this context, Now is the time [of the first quatrain] resonates with a new meaning. Now is always the time when we choose: to live or to die, to be present or absent, to grow or to decay, to expand or to contract.)

Another quality that sets this sonnet apart from the others is the appearance of the mother.

There are two mothers here, the potential mother-bride (and this figure is not so unusual in the first part of the sequence), and the young man’s mother: it is her appearance that is unique.

Why is it the mother (and not the father) who, in the young man, calls back the lovely April of her prime? The father would seem more “logical” in this context (and it is the father who, in other sonnets, fills the part of “parental figure”).

In my personal relationship with this sonnet, it was this image of the mother — for whom the young man is a mirror, a personal time machine — that generated a powerful initial resonance, the most immediate, direct connection to my own life: in the mirror of the sonnet, I recognised myself in this mother of an adult son, seeing herself mirrored in him, calling back the lovely April of her prime.

A never-ending mutual mirroring: she, seeing herself in her young son; me, seeing myself in her (and in my son). It is this is the imagery of infinite mutual mirroring that is reflected (“mirrored”) in my painting translation of this sonnet.

But as easy as it was for me to identify with this mother, it was hard to stay open and non-judgemental about the way the sonnet presents the future bride-mother: as a passive “womb”, devoid of any agency, except perhaps this wilful disdain with which she might refuse “the tillage of thy husbandry”.

Here we encounter this fundamental opposition between feminine and masculine, passive and active, Yin and Yang — expressed even in the choice of relative pronouns in the second stanza (where is she versus who is he) — mirrored to us from another, much more patriarchal epoch.

It is only the young man’s decision to procreate that matters, because nobody can possibly refuse to participate — this “narrative” clashed deeply with my modern feminist sensibilities, and the challenge of the sonnet was to see through this “historical” clash, to see deeper, beyond this “trigger”, or rather: to see this trigger as an opening, an invitation…

The second stanza is the heart of the sonnet, where the two fundamental, primal binary oppositions meet one another: Yin/Yang (feminine/masculine), and Live/Death. The peaceful “passivity” of the life-giving feminine versus the agency of the masculine “husbandry”…

But the young man to whom these sonnets are addressed — he also has feminine qualities. This boy, “master/mistress of my passion”, who looks like a woman, in whom both sides of his dichotomy are fused (and this confuses and seduces the speaker of the sonnet)… Perhaps this sonnet, too, invites us to see through this dichotomy, to look for a space that holds both Yin and Yang? And after all, it is on the willingness and acceptance of the feminine power that the young man’s potential immortality depends…

The feminine power of the sonnet also shows up in its feminine rhymes (also unusual in Shakespearean sonnets), these unstressed last syllables…

There are really two words, two images, that keep this sonnet together — mother and glass (mirror). The ubiquitous presence of mirrors was a novelty at the time (not unlike the ubiquitous “selfies” are in ours)… and this endless mirroring is presented here as an analog to biological reproduction, as another type of “replication”, in which all human beings endlessly look at one another as though looking at oneself in a mirror.

Interestingly, the sounds of this word, glass, are also repeated in the only “colour” word of the sonnet, golden. And if a colour word is present in the sonnet, this colour (almost) invariably finds its way into my painting translation — and since the sonnet is shaped by dichotomies (life/death, feminine/masculine), the painting’s colour harmony relies on the strength of a single binary opposition of colours: golden/yellow: blue.

But the heart of this painting is mirroring… its structure is loosely based on Edouard Manet’s last unfinished painting, with its mysterious figure of a man reflected in the mirror but absent, inviting the spectator to see himself in this reflection. Reversing the gender of the figures, my painting loosely identifies the viewer with the mother, reflected in the invisible mirror behind the young man — or rather, the mirror which is the young man.

The image of the young man for this painting came from the Renaissance, from Titian’s young man with a glove — and it was the first time that two masterpieces of painting, from different epochs, fused into one in my painting translation of the sonnet, giving birth to the personal experience of time-transcendence (which, since then, has become an intrinsic part of this work). This is probably not an accident, because the sonnet itself, with its mirroring through time, defies the concept of linear time…